by Chris Banks

I remember watching Robert Pinsky years ago talking about the poetry of Louise Glück, and how Glück, perhaps more than any other poet, scrupulously avoided clichés.

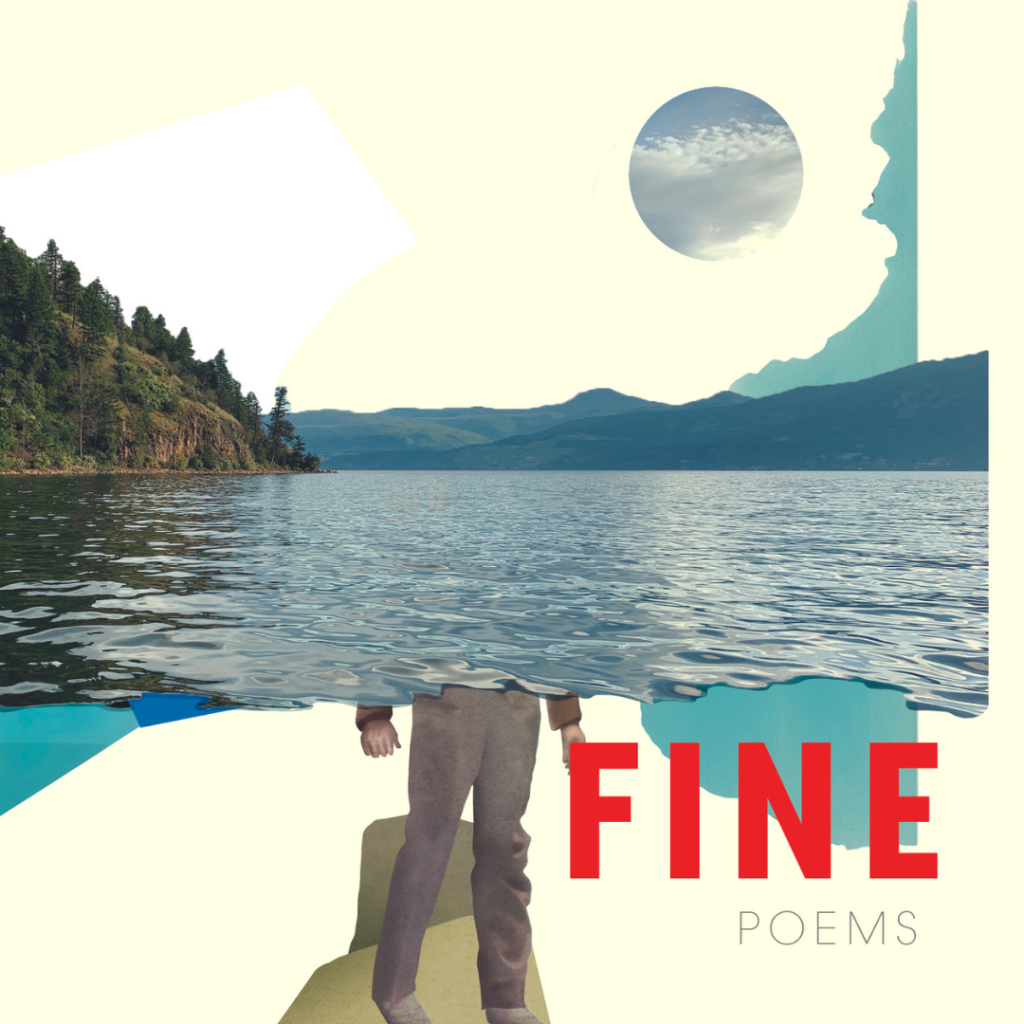

There is something about the pared down lines, sometimes no more than two or three words, in Matt Rader’s latest poetry collection Fine out with Nightwood Editions (Spring 2024) that puts me in the mind of Glück .

It is not simply in the bare elegance of Rader’s line breaks, but in his strict attention to language too, especially in his near obsessive avoidance of cliché. I have read, and reread this book, and the language Rader has found for this new collection is uniquely his own.

In the opening poem “Fine”, the speaker gives a hint at what the book is about when, during a now sadly annual forest fire season in British Columbia where Rader lives and works, he says:

I wanted to make a shift from fire to fine

its averageness, its elegance

its penalty

Then the helicopters lifted the cold dark energy of the lake

into the sky

like a chalice

The word play in these slim lines suggests a couple of readings: one, the human desire to avoid the reality of the climate crisis, of which forest fires are certainly a growing symptom, to say things are simply fine and then avert our eyes, but also two, it suggests the forest fires are the penalty, or fine, we face for such ‘outta site outta mind’ thinking: for not owning up to our responsibilities as stewards of the land.

Rader has always been a poet of observation, I won’t say Nature poet, but he takes it one step further in Fine by trying to sync up his imagination, and too human intelligence, to nature’s own intelligence – its light packets and quanta and joules of energy- to see what new understandings might take place.

Rader says at one point, “I want / new ideas, badly”, and certainly readers feel the guiding ethos of Fine is both the poet’s lonely vigil, i.e. his witnessing of reality– those places we find ourselves in this world – but also the need for clarity, the desire for understanding how our inner lives are caught, and indeed created by the weft of human thinking interweaving with nature.

I think it is this understanding that the poet Rader is chasing throughout the poems unfolding in this collection. It’s like he is asking where does the world end, and ourselves begin? And can we ever understand the outside world when at the moment we begin to see ourselves as individuals with disabilities, with work responsibilities, with memories, is the same moment we sadly disconnect ourselves from Nature?

Rader writes, “Reality is always virtual” and I take this to mean that reality is always an amalgam of what is outside meeting what is inside. It is in such moments human consciousness searches, buffers, processes, churns out new meanings and new understandings, making “some things more Real than real” as Rader writes in his poem “Real Things”.

Formally, the line-lengths are short, economical, but the poems themselves flow over two or three pages so the ideas contained within them are anything but spare. As the poems are very long, I will only excerpt some lines, starting with the poem “AutoCorrect”:

The north wind kept shoving the lake

towards the US border

whitecaps

stumbling like prisoners

autocorrected

back to lake water. That’s what the mind does

distract itself

invent things.

The sheer inventiveness of “whitecaps / stumbling like prisoners / autocorrected / back to lake water” is such a joy to read and, then the next line heavily underlines the poet’s sentiment that the mind distracts itself, uses the imagination to “invent things”. But why? To create beauty? Certainly, but also to be an ‘active thinker’. To be a participant in life. To see the world for what it is instead of through the lens of what one owns, or those ideologies one has been fed.

Like Glück, I see Rader attempting to portray the individual psyche as the lonely, thinking, dreaming, sometimes anguished, sometimes hopeful thing that it is. Like Glück, he stands at the abrupt edge between ourselves and nature, and then quietly witnesses with sharp linguistic clarity, and precise detailed emotion, the solitude of human thinking or intuition which allows us to apprehend the “shape we could not regard directly / at the centre of things.”

Take for instance, Rader’s poem “Pineappleweed”. Here, the poet further places human intuition at the centre of his thinking as he writes:

Sometimes I think

we make too much

of form. Maybe intuition

is really unspoken

desire, the sudden

wordless

recognition of

a pattern

we’d wanted

so recognized.

In this poem, intuition is a kind of human omniscience that teases out connections not readily seen; patterns “forms” hide, but that language and the imagination make known. This is not only a poetry with surpassing clarity, but it is also a critique, a verdict of our consumer culture obsessed with Thinghood, and yet also an urgent philosophy that jumps off the pages of this collection saying intuition, the imagination, these are the things that help console the human soul in times of pandemics and of wildfires.

I really loved “Fine” By Matt Rader out now with Nightwood Editions (Spring 2024), and I really hope I have done Rader’s poems justice here. Rader is one of the most important Canadian poets to come out of the last twenty years. His work is outward looking beyond the borders of Canada, but his poetry vision is also undaunted by the virtuosity of his American and UK influences. This is a work of unparalleled beauty and clarity, and all the evidence suggests this is not only Rader’s best book yet, but one of the best books of Canadian poetry in recent years.

Please go out and purchase a copy of “Fine” by Matt Rader and read it for yourself!