Reviewed by CECILIA MONTEMAYOR

host to repeat after it. My monobloc tells me I

Don’t want to live, and after months of resisting,

I say it back — to try it out, to see how it feels.

— Simina Banu, I Will Get Up Off Of

Simina Banu’s second poetry collection, titled I Will Get Up Off Of, is an experimental project that ventures to give expression to the mental battles that prevent someone from getting up off a chair. The narrator thinks about getting up, too much and for too long, coming up with over fifty illogical but totally plausible-sounding excuses to stay on the monobloc. From somewhat digestible ideas like “this monobloc but the tea worked, and the melatonin, and the weed,” to more eccentric feelings like “this monobloc but eye floaters, everywhere I turn,” Banu’s collection emulates overthinking at its worst.

Utilizing block poems whose squared form mirrors rambling notes on a cellphone screen, Simina Banu’s smart craft will tense your muscle joints, twist your gut into knots and flush your body hot. Getting up off a chair becomes a metaphor for fighting mental illness while seeking online help from influencers that offer pity and discounts, memes and podcasts that claim to understand, and many other contemporary, digital-age, services that should help but may be making things worse.

it stopped working, in solidarity, a little after I

stopped working. The tongue stopped working,

stopped saying stuff, and the nose stopped work-

ing too, but that might have been COVID. I don’t

remember when the eyes stopped working, but

it was likely September, before the stomach

stopped working, but after the lungs.

How to explain when you feel like you have stopped working? Can words alone accurately capture an experience as physical as depression? Simina Banu’s painfully meticulous writing succeeds in conveying the mys(t)ery of the distressed mind. The more I think about it, I Will Get Up Off Of is like if you asked a depressed person to describe what being depressed was like, and instead, they invited you into their head and body. A state “so complicated with so / many muscles involved. There are the quad- / riceps and hamstrings doing the heavy lifting, / and gastrocnemius muscles, which straighten / the body as it rises. But it is also important to / engage the obliques, glutes and retus abdomi- / nis to avoid overworking the legs.” While reading, I felt it, defeat weighing my body down like metal chains attached to a slowly sinking anchor, only I was sitting on my couch, and drowning in words.

Initially, Banu’s economical free verse blocks seem as innocent as cellphone notes, verbose rants that you rarely go back to, but they will pull you in as swiftly and intensely as scrolling through social media. One minute you know where you are, the next “you lose feeling in [your] thumb, and then the rest.” The poet’s writing simulates a delirious speech that develops from seemingly distracted ideas before exploding into a strangely familiar feeling. Odd imagery and unsettling metaphors begin making sense against reason. They speak to something that lurks within you, a desperate ache that craves itself—except no matter how hard you scrutinize it, and try to explain it, you’re only leading yourself further astray.

Amid the continual reality crisis of the poetic voice, the author offers a critique of the too many, too detached and, at times, borderline predatory psychological services of a modern capitalist system. Banu’s collection touches on a seldom-discussed concept: getting too much help, no longer is. For the poetic narrator of Banu’s collection, too many resources become part of the problem and exacerbate the monobloc limbo. In poem 43, the narrative voice “can’t decide who to trust” in a time of online psychics, life coaches and influencers; all promising “real, gritty solutions” (essential oils, crystals, and affirmation packages) that “will change [your] life” but “that ultimately leave[ them] feeling like / shit.” Finally, a coat specialist becomes a metaphor for mental health professionals who deny help to “mild” cases, spend too much on referrals, and end up offering inadequate care.

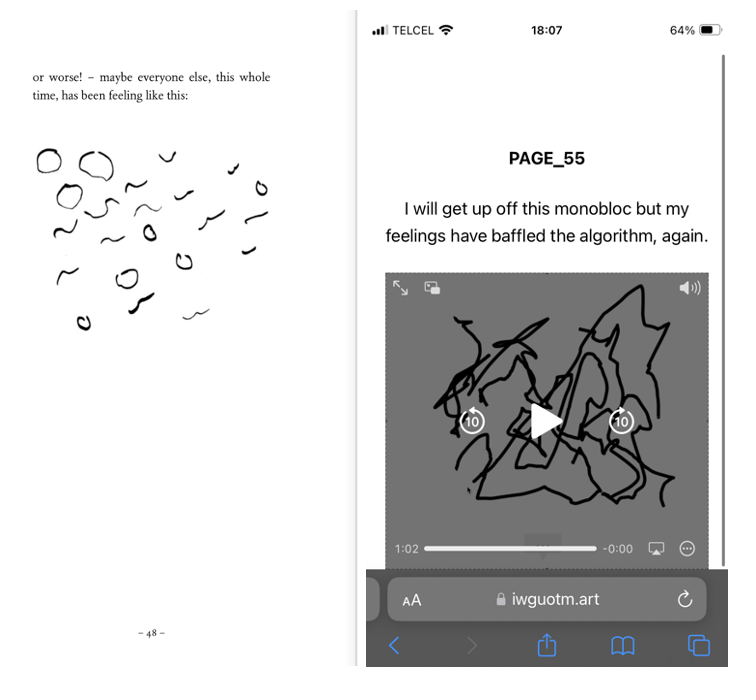

Unable to pin down their affliction into exact words, or find genuine assistance, the narrator reaches outside the physical text and into a digital maze. To access certain poems the reader must travel through pages on Instagram, Wikipedia and the web—engaging with text, audio, and video files that jointly escalate the central theme of the collection. The multimodality of the book echoes the unpredictable and winding path to help, through mental illness, and toward recovery.

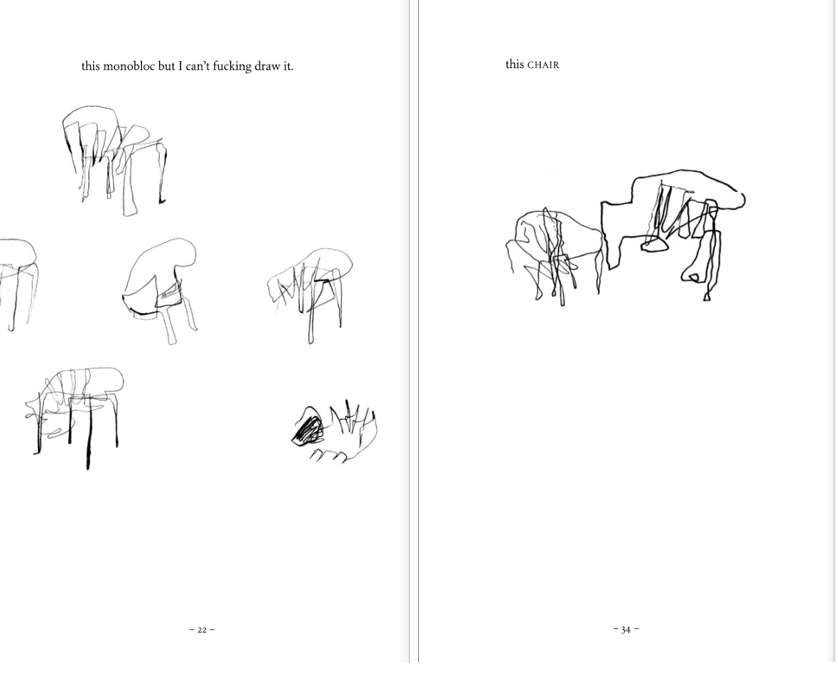

And as if none of the above fully captures the inner turmoil, Banu manages to even sketch it. One particularly notable aspect of the collection is the way the poet incorporates drawings. At first, I didn’t know what to make of them. Poorly shaped doodles of monoblocs one after another, intersecting the text with no apparent purpose.

As the narrative builds, however, the crooked and puzzling drawings, akin to Banu’s poetry, evolve into spasms of emotion, materializing the anxious twitching of sweaty and feeble hands. In this fashion, the collection quite literally grasps for expression across visual, written, audio, printed and digital mediums.

I have to warn the audience, this is not an easy read. Definitely not one I would easily go back to. But there is something to be said about capturing such an indescribable, shame-filled, and foggy state in a work as concise as a poetry collection. Containing it. Restraining it. It gives the reader a certain power, to look at their depression, dive headfirst into it, hold it in their hands, and then put it down. What’s more, for all the gaps and turns, the collection offers ample space to find the good within the bad.

You see when you are

So low

You create extra art molecules

It s just something that happens

But because art is necessarily

A hopeful undertaking

It needs to attach to a hope molecule

To exit your body as art

Even the darkest grimiest art molecule

Needs a hope molecule

To activate

What magic is it when drawings reproduce breathing and living feelings?

What sorcery is it when depression brings forth hope?

Only a poet, it seems, can summon darkness and trade it for light.

And who could embrace such an undertaking?

Perhaps you, reader. If you give this book a chance.

Just remember, it isn’t about dissecting it; it is about allowing it to guide you somewhere you need to go.

CECILIA MONTEMAYOR is an emerging writer, originally from Mexico but, currently located in southern Ontario. Interested in writing in a variety of genres, including fiction, poetry, film, and theatre, Cecilia’s work tends to fit into the speculative fiction category—and explores, among other themes, mental health stigma, conflict between the United States and Mexico, intergenerational trauma, queer love and spirituality. Cecilia is a recent graduate from the MA in English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, and holds a Bachelor of Communication and Digital Media from Tec de Monterrey, with a concentration in Film Production.