Reviewed by CECILIA MONTEMAYOR

If I were to select the bravest book of Spring 2024, this would be it. Nisha Patel’s second poetry collection, A Fate Worse Than Death, stems from a desire to expose the

deep-seated dehumanization entrenched within everyday wellness practices. This

poignant work draws its focus to the pressing need for reform in the language of

healthcare services, urging readers to acknowledge the inherent inhumanity of the

current system. Editing with a focus on wording, tone and subjectivity, Patel creates a

radical collage—altering her medical records in an attempt to vividly capture the

experience of defining oneself, and being defined, as disabled. Fearless and

unapologetic, the author shares her vulnerabilities, allowing us a peak into her

diagnoses, and shedding a light on the hardships associated with commonly accepted

diseases (like diabetes and epilepsy) and those that arise for less understood conditions (such as addiction and bipolar disorder).

Writing against shaming and dehumanization, the poet manipulates medical

documents—glazing them with an emotional and highly compassionate lens. In a short format, she makes the reader live (and drag) through ten years of mental and physical illness—across numerous therapy sessions, support groups, doctors’ notes, and medical records. “Another visit to the emergency room, and thank god I’m not wasting / their time after all.” Patel allows us to equally witness her sadness, hope and, yes, anger at both a failing body that needs love and support, and the system that makes her hate it.

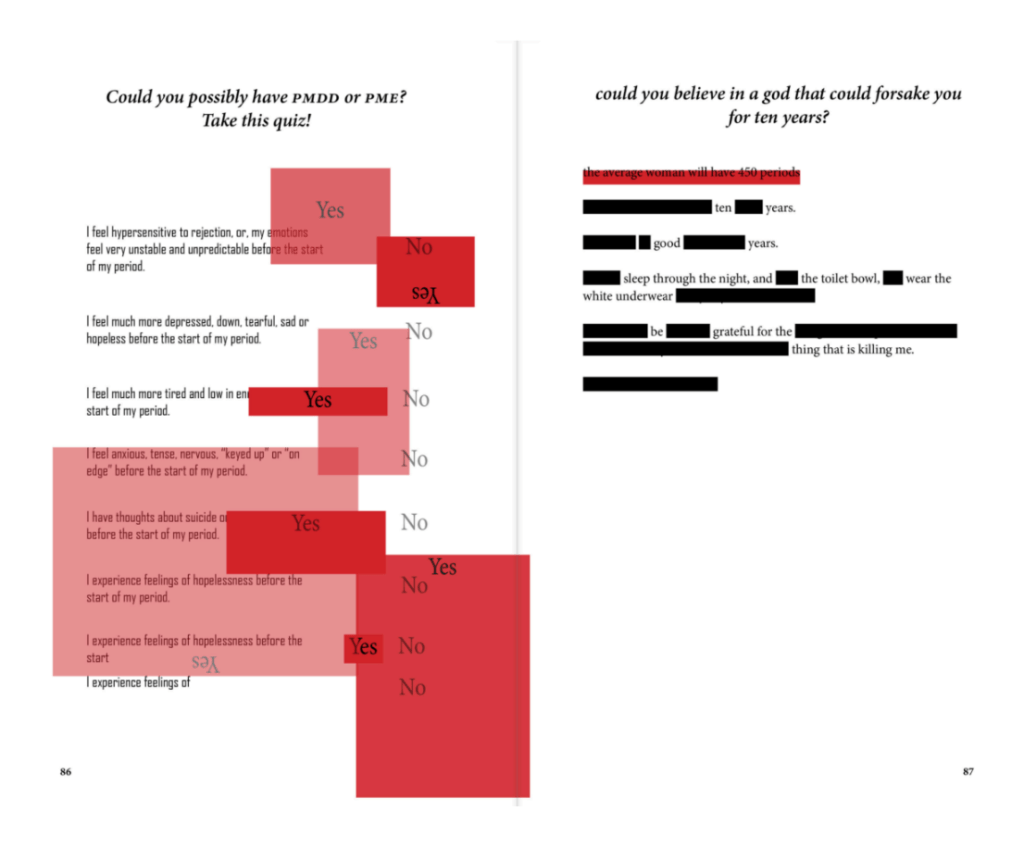

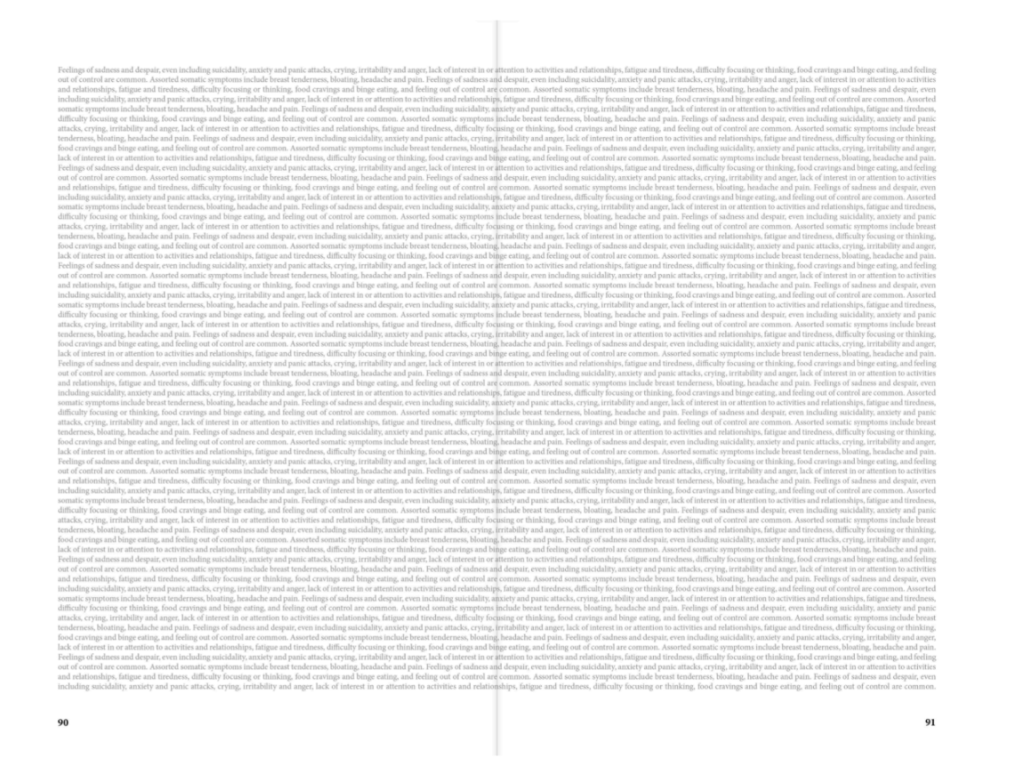

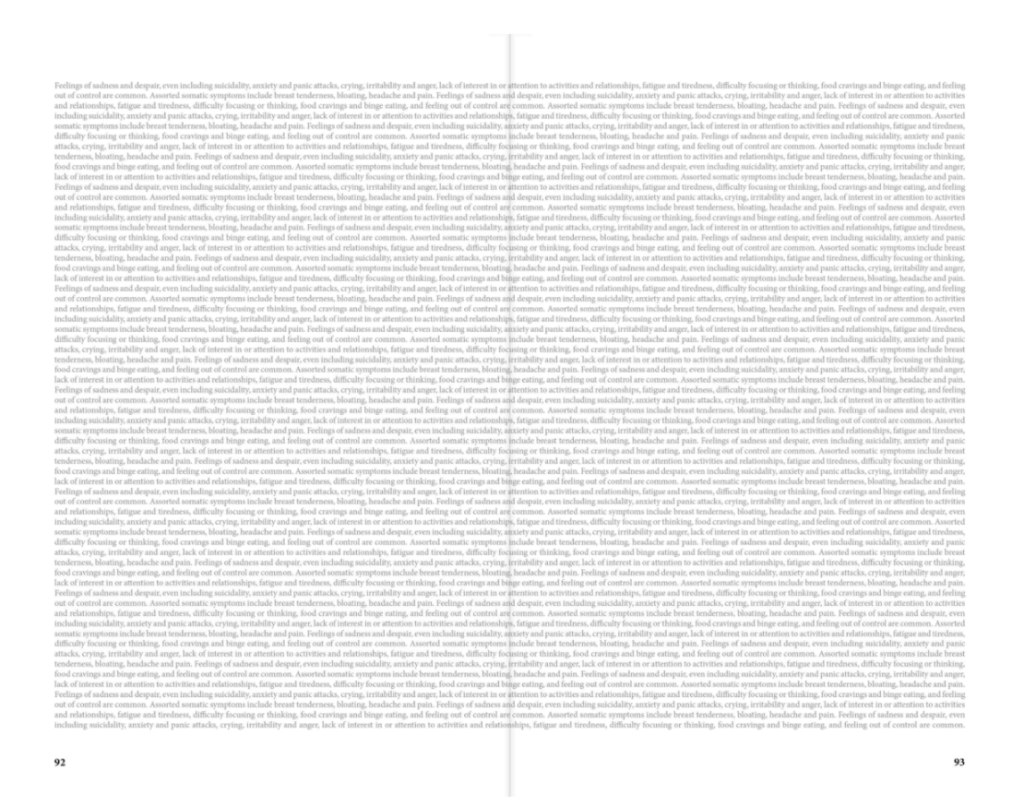

The collection’s first act of rebellion comes from its deliberate departure from the poetic form, paving the way for an entirely fresh and unexpected literary experience. In three of the four sections of the text, Patel adheres to clinical records to craft her poetry. Whether her verse takes the form of lists, emails, handouts, letters, or scans, the author is careful to transcend their conventions. The poet affixes her highly visual personal commentary to the medical archives. Smartly utilizing drawings, icons, the colour red, font size and blackout poetry, Nisha Patel gives a body to her emotional responses, the ones that doctors would rather do without, and imprints them on the medical body.

In blurry words, straightforward illustrations and revealing highlighting (and blackening) the author contains the “grief and joy of being disabled”. Nisha Patel infuses medical terminology with her confusion, pain and frustration. The diverse expressions of poetry in the collection present an incredibly challenging yet rewarding journey to read and follow. This aspect successfully accentuates how tedious and inaccessible a doctor’s verbose is. I cannot imagine the path through five diagnoses feeling any less wearing, gruelling and lengthy.

(this poem goes on for 14 pages)

In other words, the author instills a human touch to the cold, fact-based, and detached

doctor’s jargon. The collection becomes the poet’s cry against the erasure of a body that most deem a burden—and in favour of a humane view of disability that is not only mindful of the debilitating pain it represents but which also acknowledges that a disabled person’s way of life is worth the same as any.

The poet’s creative revision of healthcare documentation advocates for a radical

appreciation for the body with disabilities, as it fails, hurts, and struggles but,

ultimately, does more than survive, it lives, it loves, it feels.

and I think it’s funny that some people think heaven is just escaping from

this body instead of fighting the world to teach yourself

how to love it.

Despite the [textual] constraints imposed by medical diagnoses, the poet unlocks a boundless potential within a disabled [textual] body. Patel gifts the reader a beacon that guides to hope, presenting a positive perspective that counters the often degrading view of disability. The reader is awed by the achievements celebrated by the disabled narrator, especially given that medical assessments easily and often overlook these feats. As the patient tries to claw her way out of the strict and clean medical language, the poet’s work roots out a healing truth: it is precisely when one feels most confined by the body, that one discovers the strength to transcend its limitations. It is then that one is able to go beyond it, outside it, inside it, and to all the places in between. For, what is life, but the experience of loving with our bodies something so beyond the tangible—it repeatedly leaves us breathless, numbed with wonder, and feeling like we come from magic.

but I feel for those who have never once thought themselves invincible

never walked without shoes down a sidewalk hoping to take a running

start at flight

never lived with a mind full of possibilities for naming stars

words like episode and disorder mean nothing

as you are freed from all limitations of human body

and become one with the clouds, or the sun, or yourself.

Loving something so painful becomes a revolutionary act and the path to finding a strange bliss. In the pursuit of cherishing her disabled body, Patel is made witness to the precious life it has given her—a life that, even if it cannot be explained, or fixed, though many would want it, is worth living.

I’d rather be a cyborg than a finite and limited body

I’d rather be an IV drip and walking stick than two fast-moving feet trying

to be somebody

I’d rather be a place that holds your feelings

an object of desire

or a site of possibility

of what is, and what comes next

I want to be disabled in every universe, with you

more than I want to be remembered for something

its true.

Experimental poetry cultivates a newfound compassion for the disabled body—a feeling that grows and prospers into an experience of love, resilience and resistance. The book’s core mission evolves into a dual endeavour: fighting against the dehumanization inherent in disability diagnoses, and fostering a deep love for all forms of disabled bodies. Patel rebels against wording that: shames being ill as an “unproductive” and BAD state, filters out the “culturally approved” mental disorders, and alienates the patient to a nameless and storyless other.

Instead of swallowing her struggles—as health institutions would prescribe—Patel makes them manifest. The author’s labels show through cracks in the text, defying who is and isn’t recognized as disabled. Quickly, one begins to wonder why these terrible afflictions would ever be denied professional help and accommodations.

did you know that disability is a social construct?

that the majority define what it means to thrive

that lack is problematized as weakness

that in an accepting society we are all a little disabled

but no one is told they are less

no one is left wanting more

and when my brain does not work the way it’s supposed to

it’s okay

The author speaks for bipolar women, addicts and ill minorities who, stranded, recur to desperate devices in an attempt to find relief. Web formats function as a canvas for key poems—calling attention to internet diagnoses as they become a necessary ritual every time new symptoms emerge and as formal diagnoses remain elusive. After all, piling medical records, frequently laden with judgmental and biased perspectives, contain so few reassuring (if any) answers that one might naturally be tempted to seek elsewhere.

I cannot imagine writing this book in anything but sobs. The collection’s life force

sprouts from the author’s vulnerability. Patel invites us to read her at her most

vulnerable—confessing her battles with suicidal thoughts, addiction, and physical

decline, eternally struggling with a dying body that persists in defiance. A rebellion that appears so weak for it holds no tangible cure, yet is remarkably courageous in its relentless effort to endure.

because people like me die sometimes and no one cares

but I am lucky that when I die I will notice

I will feel a sigh of relief, I will know that I did my best, and if it wasn’t

enough, it isn’t my fault

that I tried, that trying when your body fails is a gift to yourself

I am not afraid to die, after all

I am afraid of who I might fail to be if I live in fear of death

when I google

WAYS TO SAY I LOVE YOU WITHOUT SAYING I LOVE YOU

I know that going to bed, and waking up,

is one of them.

When a whole system makes you feel less because you are disabled, Nisha Patel loves

you the more for it. Hers is a radical act of love: a curative seed. Find its healing

properties today, courtesy of Arsenal Pulp Press.

CECILIA MONTEMAYOR is an emerging writer, originally from Mexico but,

currently located in southern Ontario. Interested in writing in a variety of genres,

including fiction, poetry, film, and theatre, Cecilia’s work tends to fit into the speculative

fiction category—and explores, among other themes, mental health stigma, conflict

between the United States and Mexico, intergenerational trauma, queer love and

spirituality. Cecilia is a recent graduate from the MA in English and Film Studies at

Wilfrid Laurier University, and holds a Bachelor of Communication and Digital Media

from Tec de Monterrey, with a concentration in Film Production.