by Chris Banks

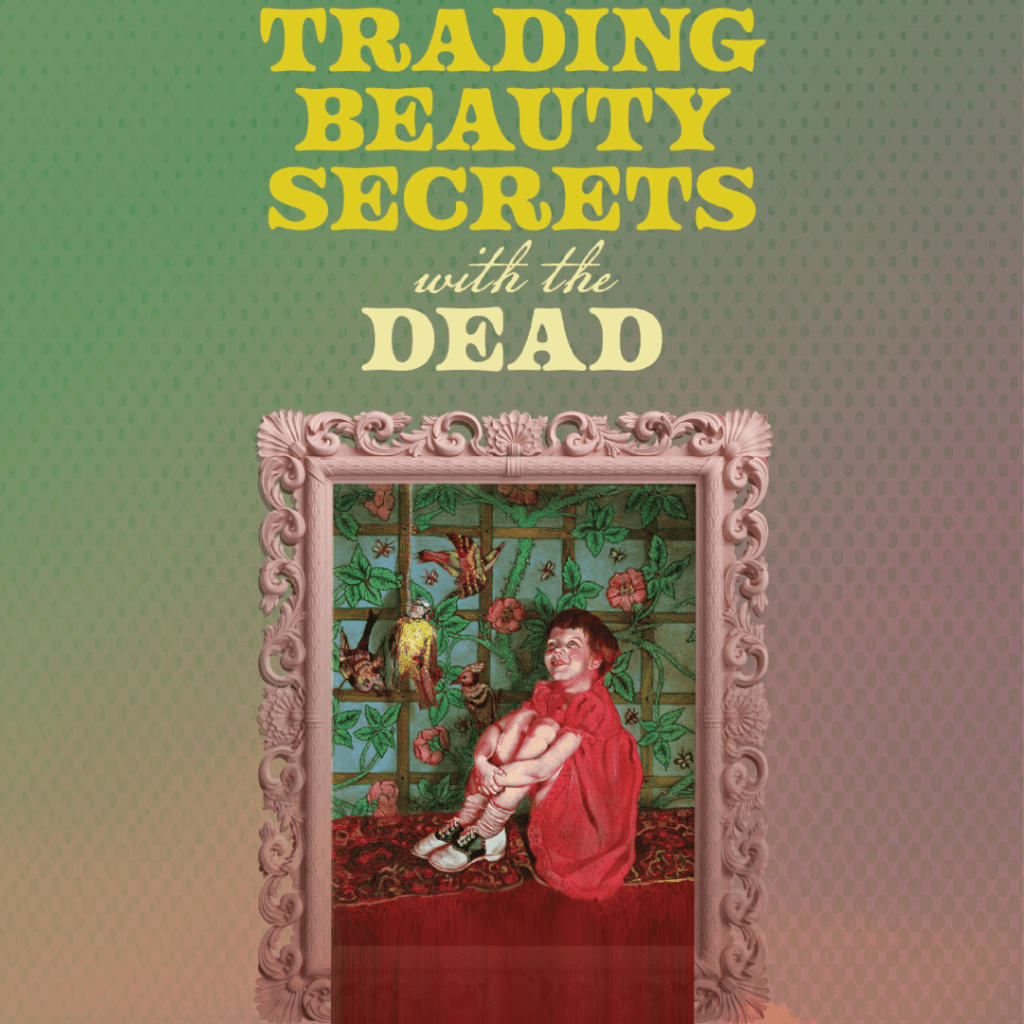

The first thing you will notice upon opening Erina Harris’s bold new poetry collection Trading Beauty Secrets With The Dead out with Wolsak & Wynn this Fall is that the Table of Contents is actually retitled “Abecedarium: The Letters” and that the individual poem titles coincide with the letters of the alphabet.

To my mind, the Abecedrium is Harris’s way of announcing that this book is going to be different, that the layout of her poems are both hyper-intentional and mischievious, and that between the covers there are traditional poems to be found, yes, but also experimental poetic forms (not my favourite word experimental, but there it is), collaged bits of fairy tales and queer/gender theory, and many questions to do with art, art, art!

So many of the poems begin with epigraphs which is a style once fashionable in Canadian Poetry, but which has since fallen by the way side (I sense the poet Harris is not very concerned with the whims of poetic fashions). When reading the first poem in the book, it took me a beat to wade through the opening epigraph, a biographical snippet about the Grimm boys taken from Clever Maids: The Secret History of The Grimm Fairy Tales, by Valeria Paradiz, before encountering the poem in its own right. The poem “Waiting Room, Part I: Letter A to Letter B” reads:

On stilts, still, Letter A awaits,

crossing its arms

across itself: Two brooms in a room

atop a shelf meet, in A, and wait,

awaiting room. In a Waiting Room

an A is first, staring in a room

inside itself. Within, it must open,

and without, A must, every bit more

and less itself stand up straight,

uncrossing from its midriff, open – (

and almost stop;

As elephantine otherness rushes in

and stays) - then wrap at tip and toe

each arm around,

to come to be Two rooms within and

out (Her forehead pressed

alongside her forehead) so

Letter B can be beside its self.

There is so much word-play, and of course sound-play too, in this poem I had to read it several times. I love the opening lines “On stilts, still, Letter A awaits, / crossing its arms” which at least for me really plays on the shape of the Letter A. This is smart, inventive and a particularly fresh way to get readers to really think about the opening of the alphabet, and her Abecedrium, but I do admit I got a little lost in “the elephantine otherness” of the rest of the poem which was harder for me to parse into meaning.

As I read the whole collection, I noticed there are poems that make a kind of profound sense to me and others which, although I might enjoy aspects of the poems—the teasing sounds, imagery, assonance, etc. – their full interpretation eluded me without looking at the notes at the back of the collection. I think this is partly by design.

This is not to say all of the poems are inaccessible, as by the time we get to “Letter E: The Education of Little Miss Muffet”, Harris presents us with a hallucinatory, albeit familiar fairy-tale re-spun in bold language and the biographical details of the real life Patience Mouffat, tricked out in bold tercets:

After Father died, I had all the wrong thoughts.

Step-Father, a Man of Science, prescribes Spiders:

For My Condition. Both Common, and Endangered,

crumpled onto teatime curds, or confined within

sentient globules of butter. One writhes in a nutshell,

when threaded at the neck. For Fever, or Ungovernable Emotion.

On occasion, they forget their lines. Some erupt

from labelled bottles he keeps all over the house. Step-Father,

Perturbed by my bouts of shrieking - (How he creeps

in my chamber at night. Those hairy legs. Tufted!

I can’t stand the sight) - then it’s Off! to the Hysterium!

Little Miss, must rest. Were he takes away my journals,

(and then nothing happens but the silk wallpaper)

leaves me only his hornbook made of gingerbread

with Arachnids, discretely beaten into the batter.

It was the most concentrated moment of my life.

I listen with my ankles in case Father is watching.

In my abdomen I make thoughts trace diaphanous lines

silken striping diagonal all the way to the sill

of the high turret window. What patience!

when climbing one two seven ten eleven then, down

the sticky rungs of the lattice sometimes the room

tilts getting mixed in with the pudding (feminine footsteps

in the hall could belong to anyone) I am spinning.

This poem is quite the performance in terms of upending expectations and meticulously avoiding cliché while playing with a much loved nursery rhyme. It also inserts biographical details of Patience Mouffat and her step-father’s medical practice of feeding spiders to her (and to perhaps other shrieking girls) which was commonly thought to cure a variety of ailments. For me, the poem works by first reading the poem, then thumbing to the back of the collection and reading the meticulous notes Harris has constructed, and then rereading the poem with the fresh knowledge gained.

This is to say I am not sure I understand the poem without the notes section but I think this is part of Harris’ approach to this collection. The poet Harris is not going to make it easy to sit back and to just read the poems as poems without reading the epigraphs, the notes, making jumps between poetic lines, between nursery rhyme and ‘real life’, between dramatic scripts and poetry, nonsense and sense, and on and on.

Perhaps my favourite poem in the whole collection is “Letter I: Intermission, The Image” which takes the Phenakistiscope as its dominant image—an old-fashioned optical toy that creates the illusion of fluid motion using human figures and a mirror. Here is the poem in its entirety:

Each and every one of her,

The same as her, or nearly. “And, so near – “

Each one is a lithograph of her.

Each one is just close enough to hear.

Each one with her paper coat, horsehair.

Twenty of her move in unison.

Nineteen hers, facing her procession.

To almost touch the cloth coat of the one

In front, but then she must move, then, her motion

Might enrage or estrange us. Untouched,

The daughters made of paper always follow.

We can’t tell which is the original.

So, daughters in the phenakistiscope

Tilt our twenty heads to the left: “Go!”

And when she tilts her head: as if we know

That in her image “Could she know for sure.“

She shifts, or shoves – “Take this,” as if to share –

To catch and hold her tight, imagine – there!

(Winding string tight ‘round her wrist). Ask her!

“Do you like to be looked at?” at Intermission.

Here, Harris juggles some pretty serious end-rhyme and meter in cinquains while giving the poem a real story, a narrative push, while allowing the reader to almost see the optical illusion of the phenakistiscope moving. It’s a terrific performance.

In Trading Beauty Secrets With The Dead, Erina Harris has scrupulously avoided the conventional and baited the unfamiliar, the atypical, the ‘out of the ordinary’ in the way she constructs the nuts-and-bolts of her lines and in the layout of her book. Erina Harris has a distinctive voice entirely her own, but which is also unafraid to lean in, rely quite heavily, at times, on ‘making thoughts trace diaphonous lines’ of dead writers, or building off of biographical snippets, or even whole other genres at times.

Trading Beauty Secrets With The Dead is not always an easy read, but it is not meant to be, and if the reader can let go of their expectations, and trust themselves to the reassuring voice of the poet Erina Harris, the collection becomes a compendium of striking poetic lines and a fascinating deep dive into misogyny and myth, other writers, other texts, most of which are all long gone.

Chris Banks is an award-winning, Pushcart-nominated Canadian poet and author of seven collections of poems, most recently Alternator with Nightwood Editions (Fall 2023). His first full-length collection, Bonfires, was awarded the Jack Chalmers Award for poetry by the Canadian Authors’ Association in 2004. Bonfires was also a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award for best first book of poetry in Canada. His poetry has appeared in The New Quarterly, Arc Magazine, The Antigonish Review, Event, The Malahat Review, The Walrus, American Poetry Journal, The Glacier, Best American Poetry (blog), Prism International, among other publications. Chris was an associate editor with The New Quarterly, and is Editor in Chief of The Woodlot – A Canadian Poetry Reviews & Essays website. He lives with dual disorders–chronic major depression and generalized anxiety disorder– and writes in Kitchener, Ontario.