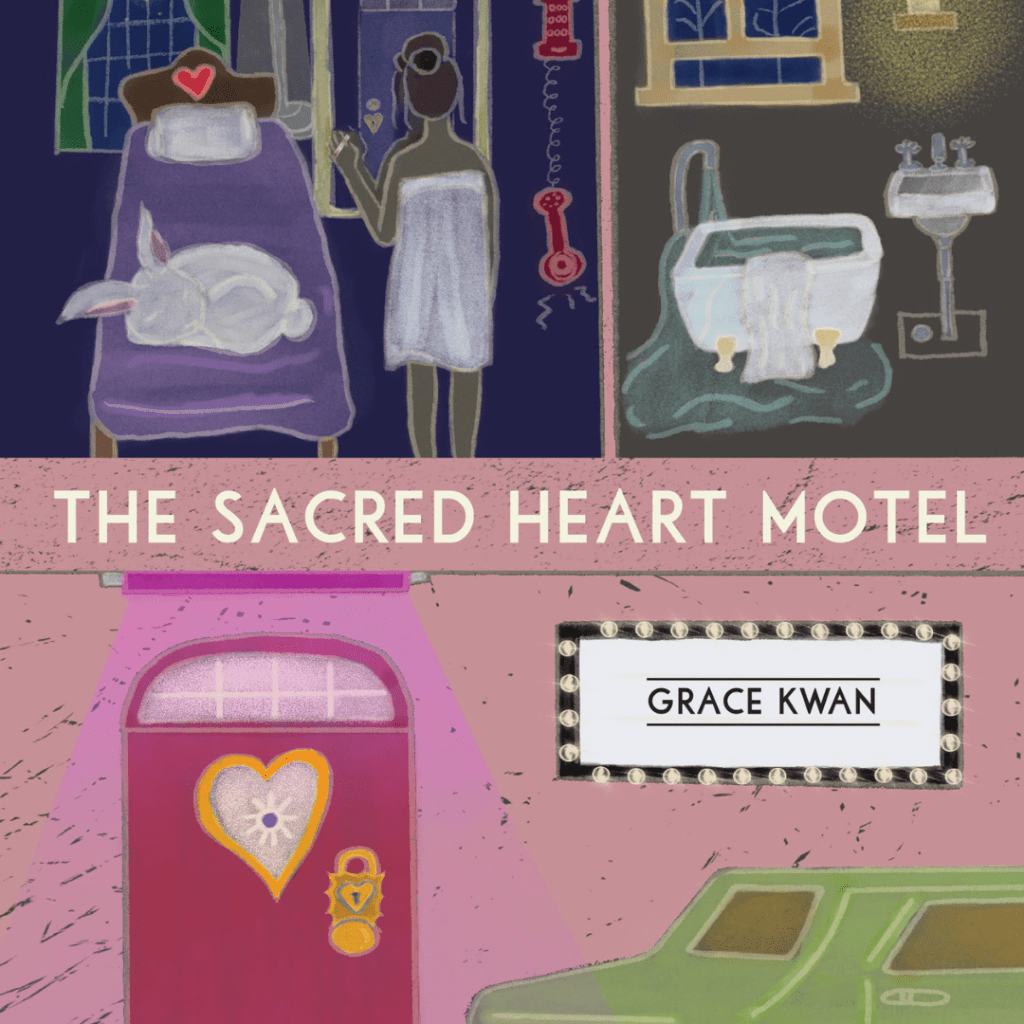

by Grace Kwan

Before my abortion in February, I sat on the balcony of a friend’s low rise apartment in a fold-out lawn chair with a blunt in one hand and a bottle of water in the other. I was focused on the blunt. It was my second or third of the night, not my last, smoked one after the other. The ember burned at its tip like a searching eye in the near-complete dark. Dead leaves in the fading blue rectangle of the swimming pool below rippled gently. My friend, in the apartment behind me, sat at the digital piano with his back to the balcony, headphones on. I listened to the keys knocking tunelessly as he played his music directly into his own ears.

After some time, when I had long started shivering, he slid the balcony door open and sat in the lawn chair beside me. My face was wet and swollen and still streaming. All I wanted was for someone to hold my grief for me. It felt lifelong and heavy.

Do you want to talk about it? he asked.

I wanted to give it to him, and for someone to understand how close to death I was and tell me that my terrible fear was worth avenging in the afterlife. I let this want build in my head until it pressed against the walls of my skull, pulsing at my temples, burning and boiling. The tears ran hot down my cheeks in the chill. The physical inability to speak when I needed to most was familiar to me. My jaw worked but stayed shut.

I arrived in Canada in 2006 with three languages in my care. I failed to nurture them into adulthood. At seven years old, my accent when speaking English embarrassed me, and I cringed when my mother conversed with white Canadians at the grocery store. I was quick and observant, already advanced in English due to my love for reading, so it took little time to incorporate the melody and rhythm of my classmates’ speech into my own. I had to be able to handle the conversations from now on.

My transformation was so whole that I never quite understood why I felt so divergent from friends who’d been born middle-class Chinese Canadians. Those friends spoke Chinese with an ease that unsettled me.

I spent as little time in Malaysia as I could. I spoke no Malay after stepping on the plane to Vancouver because there was no need to. I remembered how to say selamat but forgot the qualifiers that came after — good but not morning, good but not afternoon. I’d spoken Mandarin and understood Cantonese all my life, even caught bits of Hokkien, but I resisted my parents’ attempts to teach me how to read and write. I responded to their Mandarin in English. My favourite treats, the textures my tongue held dear — sticky glutinous pastries, snow-like sugar, the savoury grit of lei cha soup — retreated into memory like an old dream.

I started writing poetry in 2020, in grad school, when lockdowns had become routine. I don’t think I knew how much I needed it. I filled the notebooks that catalyzed the poems in my book swiftly, completing one every few months or so, stuck in a bedroom haze of vicarious trauma I didn’t yet realize I was affected by thanks to daily readings of scholarly literature about violence against people who look like me.

While writing and editing the book, even after it was accepted for publication, multiple events in my life culminated in mental health crises. Before meds, I went to work every day dizzy, hands numbed by anxiety. My unregulated responses to emotional triggers found me screaming at the stars, throwing rocks at nothing in my rich white neighbourhood. If I didn’t stay high all the time, my heart felt like it was beating in open air with no ribcage. In her novel Contents May Have Shifted, Pam Houston describes suicide as a way to break up with the world before the world breaks up with us. I wanted to spite the world and make it sorry.

The poems I wrote while sick and mad helped me to accept the losses — of voice, of belonging, of selfhood. These themes drew from the same curiosities that inspired my academic research interests in diasporas and language throughout my MA studies. Conversely, my poetic work lent a personal and reflexive dimension to my research methodologies and writing. The “unsayable” things that couldn’t make it past my throat became visible in my writing practice “in the same way that dark matter becomes visible to the astrophysicist,” as Rebecca Lindenberg puts it. Lindenberg refers to both the poet and the reader in her quote. I hope that the reader who stumbles upon The Sacred Heart Motel finds their unsayables inside. It is, at its most fundamental, a book about searching.

Even before our migration, I’d grown up travelling on planes when my parents were young and their accommodations were taken care of by my father’s acting jobs. Before the many basement apartments we left behind in Vancouver came the hotel rooms and inns where we’d stay for weeks at a time on the road in Asia. I was working as a server at a hotel restaurant when I started putting the poetry collection together, and became enamoured with the romance of temporary lodgings as sites where abstract ideas of placelessness, unbelonging, and memory could be situated in space. Behind the romance stretched a darker, colder network of stairwells that allowed staff to vanish from the guests’ view.

A character in Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World Where Are You said that a novel-in-progress is a place where your thoughts can come home to rest every day. That place, for me, was the Sacred Heart Motel. I opened the door, and it pulled me through. In its hallway my voice echoed. In its rooms I undressed. Smoked a cigarette or two.

MY YEAR OF REST & EXPATRIATION

I’m having lunch with a girl

in an eatery playing Phoebe Bridgers;

funny how we aim at politics first thing

after a breakup. I tell her I do

hate her mom but really I miss

having a mother to do my grieving

for me. The most gorgeous things

people have made are always the things

they’ve made for themselves. I curate and curate

until the words tell what I want. I still feel

childishly that the world owes me

kindness and a mother is a collector

of both clutter and debt. And

daughters— the way their hearts break,

there’s no poem in it, just the wind

screaming kiss me kiss me kiss me kiss me love me

love me love me love me

Grace Kwan is a Malaysian-born sociologist and writer based in “Vancouver,” the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. Their recent poetry appears in Canthius, Room Magazine, and others. Find them at grckwn.com.