For a long time, I’ve never considered Daniel Scott Tysdal to be a serious poet. His first book, Predicting the Next Big Advertising Breakthrough Using a Potentially Dangerous Method (Cocteau, 2006) is emblematic of the reasons why. The slight text features a plethora of pop culture detritus, but perhaps the most pertinent reason to point out in terms of Tysdal’s career arc is that Predicting’s poems are intellectually silly. Jon Paul Fiorentino once praised this book as “innovative” and possessed of an “experimental instinct”, but I’ve always felt it was a kind of stalled stand-up comedy, all premise (and some very amusing premises to boot) but no punch line. It’s the kind of book that would provoke a Canadian Literature reviewer (in this case Tim Conley) to fondly recall a Monty Python skit from yesteryear while mid-review (Conley 145).

Tysdal’s second book, The Mourner’s Book of Albums (Tightrope, 2010), albeit less self-consciously ridiculous, still retained heavy scaffolding. In a review of the book in Broken Pencil, Hal Niedzviecki wrote that Tysdal’s “[m]ore complex set-ups [. . .] are not always as successful. We are pulled into the story, but then let down by the doodled sketches on napkins and notebooks that follow. Ironically, in a book of elaborately staged set-ups, Tysdal is at his best when he reigns himself in” (58). Up to this point in Tysdal’s career, not a lot depended on an old red wheelbarrow, but rather on the trailer for the titular poem that’s currently showing at a drive-in theatre where your mom is one Thunderbird over, necking with the Fonz.

This isn’t to say that I didn’t consider Tysdal talented; there were a great many arresting lines to be found in his work. I just considered his talent wasted on writing poems that weren’t entirely comfortable buttoning down and getting on with their lives.

Something slightly shifted with his Fauxccasional Poems (Goose Lane Editions) from 2015. I write ‘slightly’ because the main modes of his poetic were maintained. Firstly, his penchant for hyper-premising his work was preserved; as the back cover attests, the gimmick of the book is for the poet to “inhabit voices not his own, writing to commemorate events that never occurred, for the posterity of alternative universes.” For evidence, just look at the epigraphs required to set up each poem that appear under every title. Secondly, and in the words of Michael Roberson, another reviewer from Canadian Literature’s past pages, this work “imagines poetry as funny but responsible” (252). In this way, Tysdal’s like a contemporary stand-up comedian aware of the consequences of punching down.

But something was different with this book nevertheless. A kind of weary sadness appeared on fauxccasion in poems like “One More Love Poem”, suggesting the real tears of its authoring poet-clown. I discovered glimpses of Tysdal not trying to hide behind a premise, a Tysdal whose heart was more compelling than his imagination. Consequently, the book suggested to me a poet who had the wrong emphasis for all these years, perhaps because he felt the need to erect elaborate defences against the world at the expense of a reader never knowing who he truly was. The premises created a distance, on purpose and by design; silliness undermined any chance at seriousness, making for a goofy – even zany – persona. Though an evolutionary leap at the level of craft, and at the level of concept a refinement of premise-play and humour, Fauxxcasional was more remarkable when it just got real.

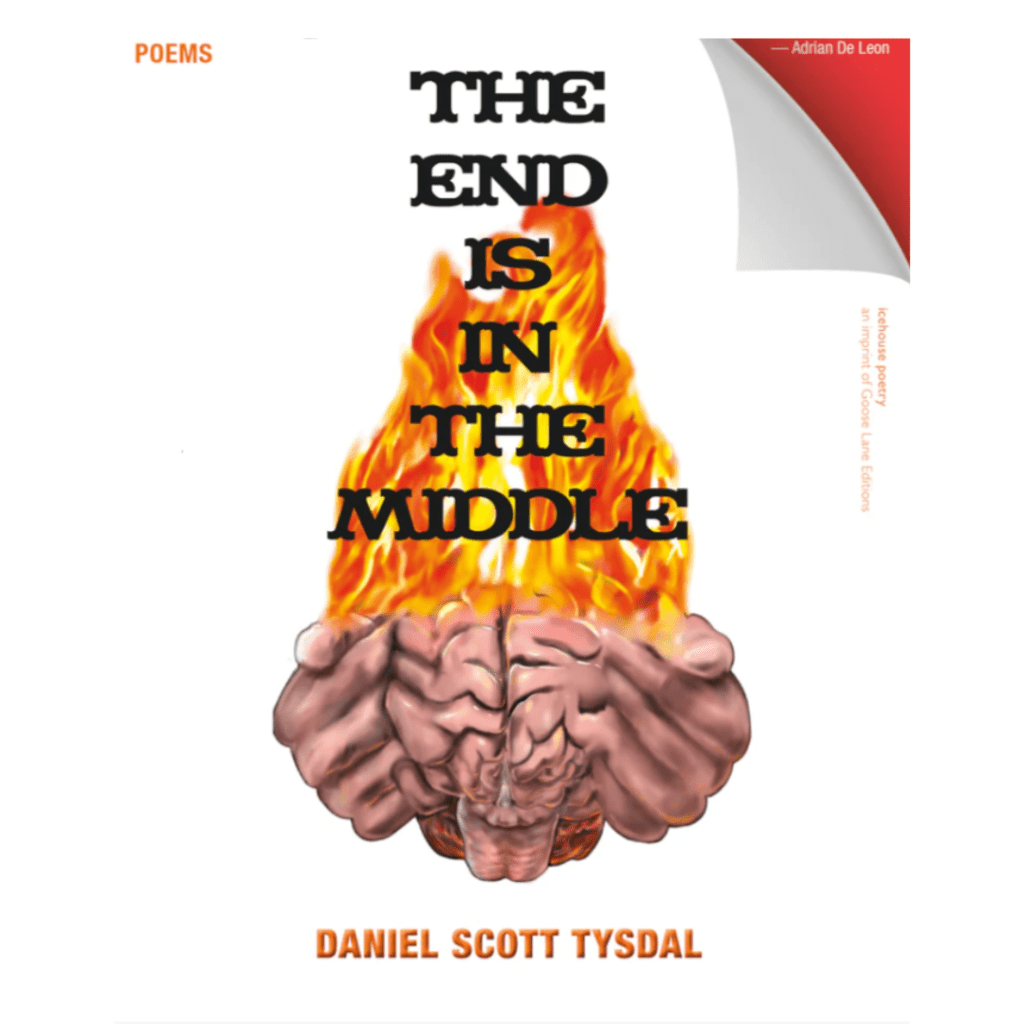

The End is in the Middle (Goose Lane Editions, 2022) represents less an arrival of Tysdal’s talent – for it was always there – and moreso a culmination of it. The tentative first steps taken in Fauxxcasional towards a more direct representation of self, of straightforward address unadorned by distraction or subverted by outrageous premise, have evolved into great strides of self-revelation. What I truly love about this book is that Tysdal didn’t get here by abandoning his obsessions with humour and with elaborate set-ups. Instead, he fused them, allowing them to inform the form of the poems but somehow also preventing them from dictating content.

To wit: The End is in the Middle relies upon the example of Al Jafee’s illustrated fold-ins from Mad Magazine. One folds the free margin of a page towards the centre and the final line of the poem is revealed. In this way, the “funny” quotient to Tysdal’s verse is supplied in terms of intellectual heritage, if not actual laughs; the “premise” quotient is also dispensed. But there’s another valence: as Tolu Oloruntoba writes on the back cover of the book, the fold-in technique “subvert[s] the effects and residues of mental illness.” For this text is entirely about the lived experience of mental illness (in this case, depression) and almost every poem is stalked by suicidality. The content rings with authenticity: I detect intrusive thoughts, rumination, negative thinking, medications, and the effects of alcohol. The dominant mood of the book is sad, its affect low, and creativity itself is presented as a force that isn’t exactly curative, but which makes existence bearable. The poems are, in a sense, with their poet as much as they are of him.

After one folds a poem, one meets a last line that, by virtue of form, boils off the rest of the poem to make for quite various endings. In some cases, Tysdal’s after a capping beauty (ie. “Bi-Lungual”’s “our / dead / can / brea / the / for / us”) but in others there is a more complex scaffolding in which the final line contains the message that is self-consciously denied in the body of the poem proper (ie. “Napkin” and “i / am / wo / rthy / of / li / fe / and lo / ve.”) Indeed, it’s the sheer variability of these final lines that preserves readability; it’s actually exciting to discover what Tysdal will do after the fold. For someone like me who’s been reading him for some time, this feels like a dividend come due. The final reveal is not a punchline, but a poetic leap. Poetry was the purpose all along.

Shane Neilson is a poet, physician, and critic who published Constructive Negativity, a book of evaluative criticism, with Palimpsest Press in 2019.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Conley, Tim. “Seeing reproductions.” Canadian Literature 193 (2007): 144-146.

Niedzviecki, Hal. “The Mourner’s Book of Albums. (Book Review).” Broken Pencil 51 (2011): 59.

Roberson, Michael. “Explode, Lie, or Fail.” Canadian Literature 230-231 (2016): 251-52.