By Chris Banks

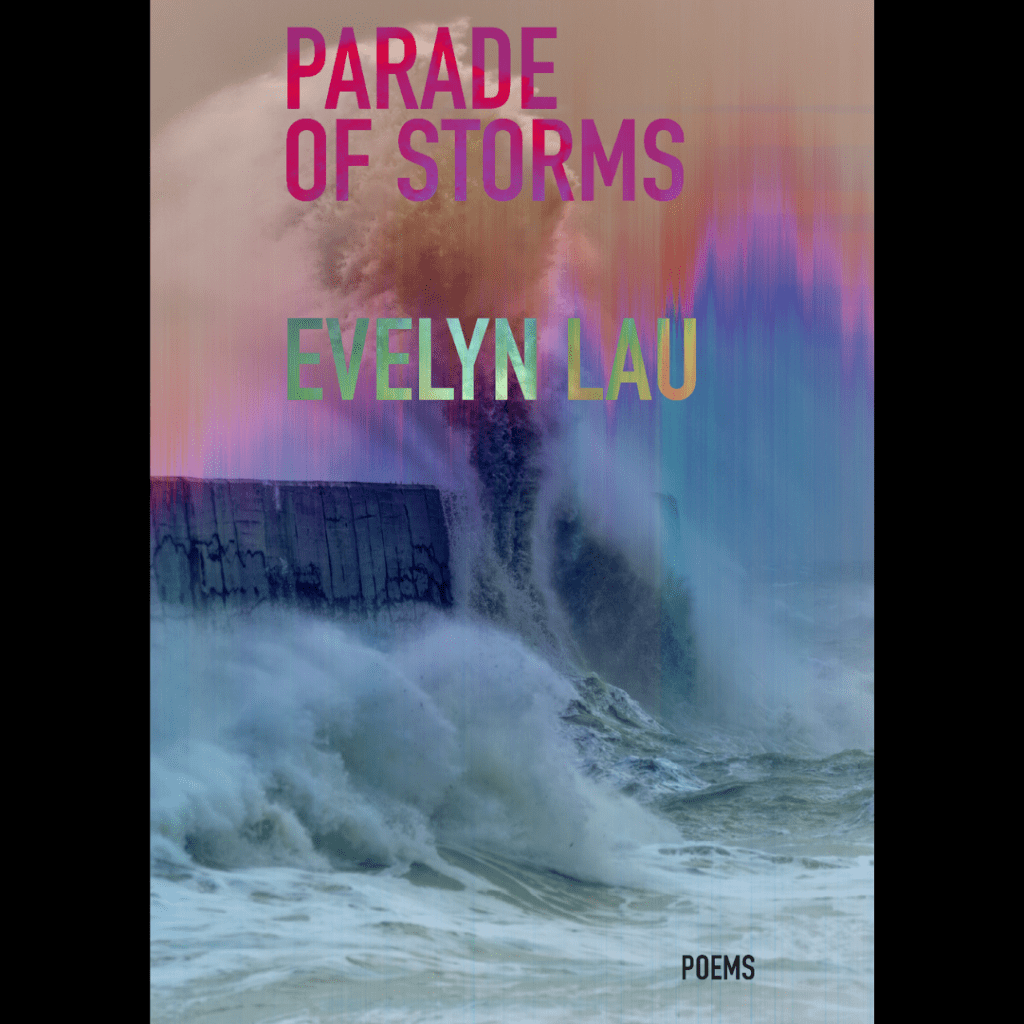

“Here there was no end to what they would spend on beauty.” Reading Evelyn Lau’s Parade of Storms out with Anvil Press this May, I weirdly started thinking about young surgeon Keats, and the phrase ‘negative capability’ he invented to explain the ability to embrace uncertainty and eschew clear-cut answers in poetry. How much of that thinking, that raw receptivity to the world came from the poor patients he saw lose limbs, the dying brother with tuberculosis he nursed (how he contracted the disease himself), the critics who savaged him, I wondered. Young Keat’s believed in poetry, in the beauty and honesty of words, to buoy his vision and redeem his life despite the petty meanness and pain this world offers, but older poets like Lau seem to be a little more skeptical, even if her poems and lines reveal she is a closet Romantic.

Indeed, I think Evelyn Lau goes to a place deep within herself in Parade of Storms that can view Vancouver’s tent cities and found needles, the container ship stacked “like a copper fort bricked against sky”, the floods, the hospices, the wildfires, the Chinese lanterns, the motel lobby signs, the young man’s “come-on” in an elevator, the skies the colour of a peach Bellini, and make it all meaningful without offering any easy answers. It is a complex poetic vision designed for a complex world.

The poet Lau writes a number of poems about a loved one dying in a hospice, and it is an unflinching gaze both tender and fortified against the inevitable. Other poems are about the effects of the climate crisis we are all facing, and will continue to face in the future. But unlike Keats, I think Evelyn Lau’s vision, one honed over many decades, is more skeptical whether words will save us from loss, or the ecological nightmares of this world, as the poem ‘Fracture” hints at:

FRACTURE First week of November, and already you’re in bed by noon. Tile-blue skies, tangerine trees — yet here you lie, nursing the invisible fracture. He said he was leaving and, three weeks later, he was gone. Say you miss me, admit it, you wrote into the appalled silence. The humiliation of how you seized pleasure from his slightest touch — was this where you began to lose him? Mornings you “forest bathe” in the urban park, past the highrise where a man flew to the sidewalk, the gore he left behind dispersed in a pile of fire-hose foam. Yes, the North Koreans are starving and the migrant caravan is crawling closer to the border and we are sick of our good fortune. You’ve lived too long in disorder, hoarding the remains — this latest flood washed the bedroom contents into the living room, where heaps of clothes and soaked papers now form a kind of shoreline, a ragged littoral border. A friend calls from California — Come with us to Mexico, say yes — but you turn away from the glare of chlorine, bowl-shaped drinks flavoured like watermelon and bubble gum. You say thank you, say no. Read poems by lamplight in the 4 PM dark. Consider what can’t be redeemed, what’s left. I love how this poem speaks to me, the way the poet Lau contrasts what I imagine is the end of a relationship with the human pain of others–starving North Koreans; a highrise jumper–making her sharply enjambed lines read to me that life is struggle amidst pain, or maybe its even more self-critical: how dare one feel such loss when so many others are suffering? The flood of the living room in the poem is just one more setback to bear making the ending of the poem that much more poignant. I read that last line almost like a question: does the true gold of our poems “redeem” the heartaches or bad choices we make, or are we merely fooling ourselves?

At another point in Parade of Storms, Lau writes, “ My life’s work has perverted me” which is another sentiment that drops like a depth-charge inside of me, a poet in his Fifties with no other noticeable skills or talents except teaching, and writing poems. In yet another poem “Low Country”, Lau writes, “Maybe I never understood / another creature’s pain, blinded for decades /by my own” which sadly I understand too, as pain can be its own opiate to a poet. But the truth is words, the right words, do offer up a measure of hope amidst the sudden emergencies and difficult silences that overtake writers and creatives who place so much of their self-worth in what they do. Check out the poem “Summer Break” that takes up this theme:

SUMMER BREAK

with a closing line by Rainer Maria Rilke

These sapped days of summer, swollen with indolence —

you’ve shrugged off that extra layer

of meaning, the poems that knit a skin

between you and the flayed world. Words, words —

why add to the clutter, when self-help books say

to take your life down to the studs, as if your life

were a room to be emptied, gutted? Both the physical

and digital worlds stacked to the ceiling, the cloud,

with words, and look where it got us.

Maybe this is the wisdom of surrender, or more

likely the lure of easy pleasures —

Taco Tuesdays, backyard barbecues,

weekend jaunts to the timeshare. Months

without precipitation, and the air puckers

with the perfume of back alley dumpsters.

Screens flicker with forest fires roaring

through the mountains, bruise-coloured banks

of smoke, flashes of flame. In Europe, in America,

tourists limp past fountains and statues,

fanning themselves, haloed by haze, humidity.

If they stumbled on the sidewalks, their braced palms

would fuse to bubbling concrete. But we do our part —

separate plastics from glass, organics

from landfill, in our small-footprint condos.

When the fire alarm gongs at midnight, we trudge

down the stairwell in slippers, the outer air

lukewarm, sludgy. Firefighters muscle past the gates,

slung with hoses, and the realization clobbers you

like a crow digging its claws into your scalp —

all summer you’ve written nothing, there is nothing

that makes you worth saving. Neighbours yawn

in the ashen half-dark, eyes down, texting.

A flashlight beam scissors back and forth

a shuttered suite. Who, if I cried out,

would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?

Maybe the angels have no ears, but I certainly hear the clarity of Evelyn Lau’s arresting voice in Parade of Storms asking if the words, the words we carefully write, are worth more than the pound of flesh every honest poem or hard-won book takes from us. Lau doesn’t offer any easy answers, but the poems in this collection are tightly controlled, the images exacting, and they precariously balance the poet’s life experiences against the backdrop of ecological and human disasters we all face, which makes me able to write here that Lau’s experiences have given her the humility and the awe and the precision true poetry requires. I really loved this book, and I hope everyone picks up a copy at their local bookstore!

Chris Banks is an award-winning, Pushcart-nominated Canadian poet and author of seven collections of poems, most recently Alternator with Nightwood Editions (Fall 2023). His first full-length collection, Bonfires, was awarded the Jack Chalmers Award for poetry by the Canadian Authors’ Association in 2004. Bonfires was also a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award for best first book of poetry in Canada. His poetry has appeared in The New Quarterly, Arc Magazine, The Antigonish Review, Event, The Malahat Review, The Walrus, American Poetry Journal, The Glacier, Best American Poetry (blog), Prism International, among other publications. Chris was an associate editor with The New Quarterly, and is Editor in Chief of The Woodlot – A Canadian Poetry Reviews & Essays website. He lives with dual disorders–chronic major depression and generalized anxiety disorder– and writes in Kitchener, Ontario.