The following email exchange took place in late March/early April 2025 between poets from the MFA Creative Writing Program at The University of British Columbia Okanagan. UBC Okanagan is located on the traditional territory of the syilx/Okanagan people.

PARTICIPANTS

The author of six books of poetry, MATT RADER is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing

SLAVA BART is a recent international graduate whose poetry thesis, Do Suns Dream of Hummingbird Looms, explores worlds within worlds and genres within genres in several braided sequences.

The author of the chapbook, “Between Two Valleys, A Lake,” (forthcoming from Anthruster Press), VIVEK SHARMA is a recent international graduate who writes about dual places, dual cultures, from the foothills of the Himalayas to the land of the syilx/Okanagan peoples.

TOSH SHERKAT is a settler-of-colour of Persian and Doukhobor descent, a poet, and a recent graduate of UBC Okanagan’s MFA program.

JESSE NORMAN is a settler of English and Irish descent, born & raised in Comox on the unceded territory of the K’ómoks First Nation, whose poetry has appeared in CV2, Unlost: Journal of Found Poetry & Art, and The Malahat Review.

Born on the traditional territory of the Cree, Dakota, Nakota, Lakota, and Saulteaux (or Regina, SK), MEG REYDA-MOLNAR is in their first year of the MFA program. They have a degree in chemical oceanography.

AMY WANG is a Chinese-Canadian MFA student whose work is forthcoming or published in Off the Map, That’s What [We] Said, Paper Shell, The Goose, and more.

Hailing from Prince Rupert, a coastal city on unceded Ts’msyen territory, NICK KUCHER is a gay poet of Ukrainian and English descent in his first year of the MFA program.

MATT

Spring 2025. A powerful colonial nation threatens the existence of the nation state of Canada. What does it mean to write and write about Canadian poetry? What does the nation state of Canada obscure, erase, or suppress in its poetry? What contribution does the nation state of Canada make to the engagements, celebrations, and melodies of its poetry?

SLAVA

In the essay “Land Speaking” Jeannette Armstrong says: “By speaking my Okanagan language, I have come to understand that whenever I speak, I step into vastness and move within it through a vocabulary of time and of memory. […] To speak is to create more than words […] it is to realize the potential for transformation of the world”.

I came here by repeatedly moving from vastness to vastness, the one I am most familiar with becoming an in-between at once hermetic and boundless, Russian, Hebrew and English three of its many axes of space animated by a dimension of time that is still waiting for the language that will capture its texture. I feel compelled to create a personal map of this landscape, make new memories, find resonances between here and a variety of theres, a way of relating both to a place strange to me and to familiar places I have left behind, the world at large, seen anew from here. When I came across Tim Lilburn’s book of essays Going Home in Nancy Holmes’ office, I was moved by Lilburn’s reaching out to a Scythian monk, John Cassian, for spiritual authority, as a way of coming home in Canada via Thrace, the home of Orpheus.

When thinking of Canadian literature, I tend toward this open mesh of many names, a place of places for poets to name and rename, without ever exhausting it.

TOSH

I’m compelled by your reflection on renaming, Slava, and I feel as though perhaps I have another story of transformation to share.

My grandmother, who immigrated to Turtle Island from Iran shortly after Mossadegh was ousted from office, often retells a story of my father’s childhood. Goaded by a family friend, she signed my father up in junior hockey because ‘he was to be a good Canadian boy, and good Canadian boys play hockey.’

Of course, this assimilation into the Canadian identity wasn’t just a matter of playing hockey. Both my father and I don’t speak Farsi, don’t know cultural customs, and have little connection to Iran.

What I find curious is that my grandparents left Iran because of the impending imperial forces coming to claim the oil reserves of the region–the very same imperial and colonial business Canada has on Indigenous lands, a business which they use the Canadian identity to justify.

When I write about my own (Canadian) poetry, I feel very aware of these contradictions. I’m thinking about a poem I wrote in which the speaker jokes about how the word “fig” in Farsi sounds like “anger” in English, but they “don’t have a story about that.” This loss to the engine of assimilation is double-edged: a loss that reproduces a need for belonging within a story; and, a lifeway (or story) generated and cultivated by the Canadian border, separated from autochthonous Indigenous sovereignty—and so the base of my poetry becomes in relation to the Canadian border.

JESSE

I can’t help but recall an Introduction to Canadian Literature class. We read Catharine Parr Traill’s The Backwoods of Canada among other texts. Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill’s texts were both published before ‘Canada’ came into being as a nation.

Their books detailed a settler colonial experience, often through diaristic or epistolary prose, that consisted of homesteading on land they articulated as being ‘terra nullius’ or ‘nobody’s land’, meeting and trading with other settler communities, Americans, and Indigenous peoples Catharine posited would disappear from the place, purporting the common cultural myth in Canada of ‘the vanishing indian’.

Moodie and Traill’s books were marketed in England to attract perspective settlers to come to ‘Canada’, a real-estate literature marketing stolen land. Five years ago, Leanne Simpson’s book Noopiming was published, the title being Anishinaabemowin for ‘in the bush’, a reference/rebuke to/of Susanna Moodie’s book Roughing it in the Bush.

If ‘Canadian Literature’ is an engine built from story-brochures that called for the violent colonial occupation of Indigenous lands to find a ‘new belonging’ then has the objective of this engine changed? Has the course been satisfactorily altered?

CanLit is now made up of a great diversity of narratives drawn from a more and more diverse authoring base, but if this engine is still an arm of the ‘Canadian’ nation state, then should we not still question its intended direction and output to fashion an imagined ‘Canadian identity’?

We’re witnessing now the reactionary nationalism that’s building in this country in response to the current socio-political climate in the U.S. The project of Canada the nation needs to be unified and galvanized in its settler belonging to this land; CanLit is adept at doing so and this American assault will encourage it to proliferate and evolve its means.

I’m not interested in aligning my writing with this engine.

MEG

I, too, feel wary of attaching my work to such an engine, and even more so within a time of resurging nationalism. What is absent in that resurgence… it feels like a missed opportunity to explicitly or concretely disavow specific things we see as problems. Where we might have said we stand against anti-trans policies, increased surveillance, deportation, de-funding of all kinds of valuable research, we said instead “we are not America”, which is both vague and narrow. Not only does it not come to terms with what this statement might deny (the ways in which these nation-states are similar), but it abandons colouring in the longing that this statement could foster. We stop our thinking by establishing a binary.

I wonder, is there something specific in the way being on this particular section of the continent makes us shape sound? It kind of seems impossible to me that such a thing would exist without being overwritten by specific regional influences, more than the broad heavy header of “Canada”.

It also makes me think of how one could imagine a unifying rhythm as emerging from these lands only if one thinks of nature as separate from culture, or more plainly: if one conceptualizes land as something static and not composed of relationality. Like one could say, oh Canadian poetry is unified because at the bare minimum we all occupy this particular space on the continent—but obviously that doesn’t account for what I would feel is more determinant of how we write: how we feel about the space we occupy (emphasis on the occupy).

SLAVA

I am very interested in poetic rhythms which seek to avoid being subsumed by accumulatory narratives. Sasha Sokolov, born in Canada, grew up in the USSR, published a nonconformist work, left to live in Israel, Europe, and eventually British Columbia. His first book was the long prose poem A School for Fools, a story of fractured memory told by a character with a split personality. He continues to write in Russian but doesn’t publish. His visionary work of multiple entangled voices, as well as his invisible presence here have been a significant influence.

The visionary strangeness of “outsiders” has been important to me, like the writings of Louis Wolfson, “a student of schizophrenic languages,” his homophonic and etymological translations from English into French, Russian, Hebrew and other languages.

Both writers are in exile from their homes and languages. Russian speakers in Kazakhstan became exiles after the collapse of the USSR. In Israel, I persisted in writing in Russian. In a country founded on sacralized memory, I found it strange that I was expected to renounce, forget and assimilate. But failed attempts to reconnect with my father in Moscow and my alienation from Israel made me choose another language. When I write in English, I am always aware of not writing in Russian.

In “Learning the Grammar of Animacy,” Robin Wall Kimmerer, in a way reminiscent of Louis Wolfson, remarks on the confluence of meaning and sound between the Indigenous word “yawe” – “the animate to be” – and the Hebrew Bible’s name for God – Yahweh, what is, what shall be. Exile in Yiddish is golus and reminds me of Bruno Schulz, who thought all language is already in golus, but could be brought back from it through poetry:

“the word strives for its former connections… And this striving of the word towards its matrix, its yearning for the primeval home of words, we call poetry. Poetry happens when short-circuits of sense occur between words, a sudden regeneration of the primeval myths.” (Letters and Drawings of B Schulz, p115).

Borders create a sense of security and home. Borders exclude and deny, creating divisions and conflicts. In a sense, all borders are a form of exile – from the space outside them, the physical and imaginative spaces of trans-border alternatives.

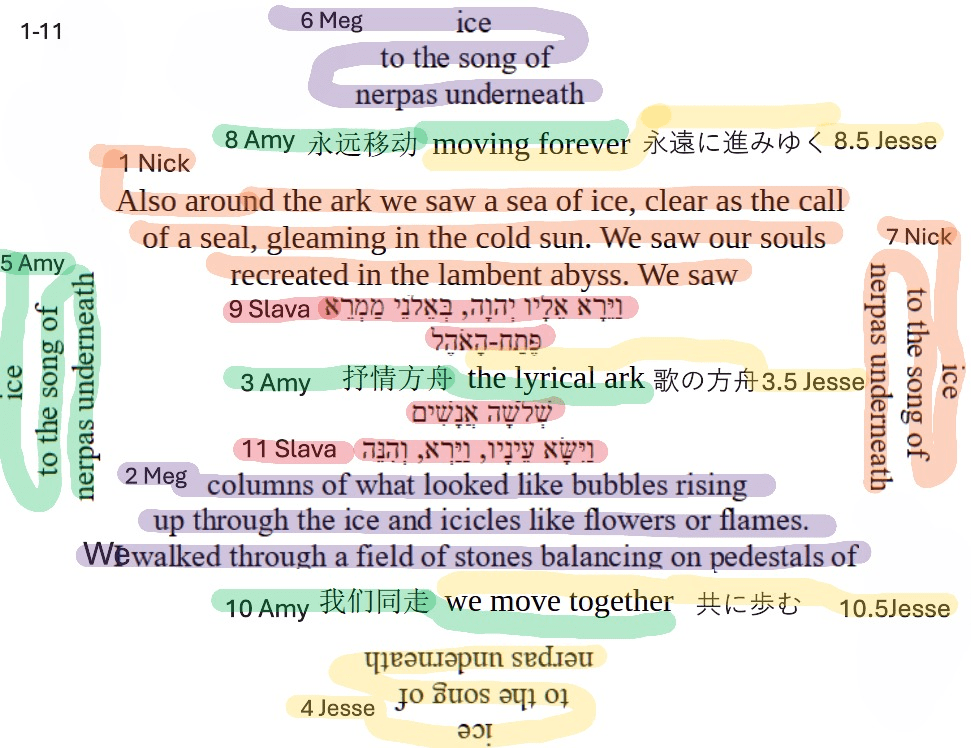

Perhaps yawe/yahwe could be one name for a beyond for us to return to as poets from our various borderlands, to “step into vastness” of entangled voices, moving “through a vocabulary of time and memory” toward transformation. In my thesis, a poem and a photograph link several languages and landscapes: Abraham’s three messengers by the oaks of Mamre is nested within a description of frozen lake Baikal, linked in the photograph to smoking Wood Lake in winter. The play of light and shadow suggests, for me, a white birch, an Eastern European symbol of home. Water glimmering around the branches of the tree suggests a burning bush:

VIVEK

I quite like the idea of being a recipient – of gathering, holding, sharing – and I think seeing something precedes receiving something. In a poem I read many years ago, Agha Shahid Ali sees Kashmir from New Delhi at midnight. It’s the early 1990s and Kashmir is under siege, war-torn, burning. Shahid sees the story of a young boy Rizwan who is dead, and towards the end of the poem, “snow begins to fall / . . . like ash. Black on edges of flames [. . .] / the homes set ablaze by midnight soldiers. / Kashmir is burning:” And an innocent boy, Rizwan — one out of the many thousands, in several neighborhoods — is dead.

And in this dazzling light, the poet from New Delhi can see another city far in the distant valley adjoining the Himalayas, a “city from where no news can come.” Shahid sees Kashmir on a curfewed night. He feels the pain. I think of that image — trying to see Kashmir from New Delhi, a border of distance and violence, rupture. What borders are we writing from, as we write ‘Canadian’ poetry?

What lies beneath the veneer of that adjective — a newfound patriotism, a seething resistance? What lines, erased and redrawn, allow some voices to resonate in the halls of academia and literary magazines and grant-guzzling tea parties while others lie scattered across the floors and washrooms of fast-food chains? Would Agha Shahid Ali — who refused to be labelled as an Indian American or South Asian even and simply called himself a Kashmiri poet — would his ghazals have survived if he were writing them from a valley such as the Okanagan today?

I say this only as a trespasser, measuring precariously my steps across the vast North American literary landscape, writing in a language that’s not my own, writing oftentimes in forms not my own, with a certain sense of un-belongingness to this land, its poetics, its formal imagination.

MATT

How then do these ambivalences, contradictions, discomforts and oppositions influence the poems you make? How does it feel then to have certain themes, forms of looking, practices of relating, and ways of identifying in and through your poetry rewarded and prioritized by government supported infrastructures such as publishing, granting, academia, and literary prizes?

AMY

The general question, “When does poetry become Canadian?” is important. I want to say this is a double bind, especially for diasporic writers.

Writing may be produced in response to Canadian historical injustices. This is true. What’s also true is how these injustices are the cause for such artwork. Would this writing still exist without all that’s happened, specifically in “Canada”? Is this what makes the writing “Canadian”?

Going further—this writing is also created for (intentionally or not) people who’ve been affected by the same injustices. Yet the perpetuators of injustice are now picking up the work to evaluate, validate, and reward. It’s an overarching contradiction.

My poetry also speaks about this. In an upcoming anthology with Bell Press (Off the Map), I have a poem titled “kōng shǒu (empty-handed).” It’s critical of the Chinese-Canadian ‘canon’ within Can-Lit. I try to situate my mother’s experiences within it:

“locating you: / history full of laborers, railroad / workers, gold miners, cantonese immigration— / but mama, / when you arrived from your / north, more familiar with flour than rice, countryside than / curbside— / it was long after the head tax was gone.”

My criticisms do acknowledge how Canadian literature has a spot for Chinese-Canadians. I can’t deny the importance of that. I’ve been writing about familial experiences in rural Northern China, and much support comes from Canadian grants/scholarships. I’m grateful for this. But every past injustice reminds me how things can be conditional.

It’s a difficult situation. Again, call it the double bind.

VIVEK

I think to some extent our critiques of a nation-state and its values are also being informed by the same values under critique. The idea of inclusion and exclusion, of diversity and quota, of grants and studies, these distinctions and divisions do inform the kind of choices we end up making — sending our work to the same institutions, getting acknowledged by the same.

And for those of us who write in borrowed tongues, in second and third languages, writing and editing over and over, betrayed by the fact of not being born into the language, of being eternally unsure, there’s always a risk, of being second-class. But I want my poems to dare, hold dual things: coherence and discord, linearity and breakage, race and not-just-race. A poetics of rupture, as Shahid might have said. The kind of poetry that ruptures because of two forces, two tensions — personal and political, America and Kashmir, poetical and sometimes polemical.

Shahid was a “refugee of belief,” caught in the Hindu-Muslim conflict. In contrast, I feel like a Joycean self-exile, seeking creative freedom and a livelihood in Canada. My sense of alienation in Kathmandu—a place I love yet needed to leave—drives this temporary rejection of my nation-state. There’s this word, anadi, in Sanskrit, meaning without a beginning, without an end.

As an outsider, as an exile, I ask, is it possible that the most radical act of writing ‘Canadian’ or ‘Nepali’ or ‘Nepali-Canadian’ poetry would be to refuse to write it at all, to refuse to let it be claimed by a nation-state that cannot fully hold its vast, unwieldy, beautiful contradictions, its necessary discord, its heterogeneity.

I’m looking for something anadi, endless, a refuge in poetry, the only liberated zone, the true homeland a poet can claim (to borrow Ranjit Hoskote’s words).

“One must wear jeweled ice in dry plains / to will the distant mountains to glass,” writes Shahid, but by the end of the poem, “I See Kashmir from New Delhi at Midnight,” he is not sure if he can will anything. So, he ends with this image. He says he has tied a knot with a green thread at a mosque, and he wants to untie it only when the war is over, “stunned by your [Rizwan’s] jeweled return,” he adds. But Rizwan, the poor boy, never returns from death. There’s no news and Shahid is back in New Delhi, when he sees “men coming from Abodes of Snow / with gods asleep like children in their arms.”

MEG

I agree with you, Vivek, in your thinking that our critiques of the nation state and its values can also be informed by the same values under critique. Especially in the context of our poetry being selected, tailored for a magazine, sponsored. I am hopeful (often against my better judgement) that, as Judith Butler says “the map of resistance is not simply the underside of the map of domination”, meaning that although it may be true that we may stumble upon and through the ways in which our thinking and our poetry might still ‘value’ the things that Canadian poetry does, in our desire always exists the potential to overcome this (over and over)? Being informed by similar values does not necessarily denote doing away with all adhesions, I guess.

I try to deal with these questions in my work by escaping into a mode of longing. In my poem, “Kettling”, I write:

“Can we go? Can we go yet?

The wind is here. Can you feel it?

It’s a hundred and fifty-five kilometers

of [otherness]

For us for us for us for us for us for us for us for us for us for us for us”

In a similar vein, in “Eden”, I write:

“I wanted to go beyond the state.

You could run

and it wouldn’t be the easy way out. We would

carve hundreds of tiny wooden boxes and

fill them with good space.

The top shelf stuff.”

Both passages I think are wrestling with trying to exist within the potentiality of a beginning rather than an ending, an expanding rather than a closing down. Are they specific enough? On the one hand: “illegibility, then, has been and remains, a reliable source for political autonomy” (James Scott, from Seeing Like a State) but on the other, I don’t want to veil too much the very real ways in which I want the world to change.

I think poetry is positioned to deal with the affective experience of existing in the complicated web of positionality, citizenship, individual history, borders, affiliations with its ability to hold things in tension, to say nuance. Vivek, you express this as a refuge, a liberated zone (from Ranjit Hoskote), and I wonder—through our poems, do we make this space for others? (Maybe an irrelevant question for an essay about poetry but) are there other places beyond poetry that this space lives?

Like Amy, I feel both grateful and worried about the forms of sponsorship available for poetry. It touches on the question of if one feels they can help make change from inside an institution. How big can that impact be? How might one measure the impact of one’s poetry in the category of Canadian poetry?

I left science largely because I felt my career choices were corporations performing some manner of resource extraction, or doing science to serve governmental interests–which can range from conservation to again, resource extraction, or even, performing the laborious, time-intensive, multi-year climate studies which (almost) never result in impactful policy. But by removing myself, I also removed myself in part from the conversation and (some of) my investment in figuring out the answer within that specific workspace. I think I bring these questions to poetry, but I’m not sure that poetry, without an interdisciplinary aspect, has these answers for me.

I don’t feel like my subscription to Canada has been put to the test as much in terms of the world of writing and publishing—I feel like my questions, so far, are more welcome, in the arts—but I also haven’t been here very long. I don’t feel like I know the waters enough yet to say anything definitive. I will say that the last year of my undergraduate degree was the first time I heard anyone say anything about the colonial implications of science within a classroom setting—if conversations can be a measure of how much questions about nationalism, Canada, and resource extraction are seen to pervade the consciousness of a particular group.

TOSH

I think what I feel when I write is a haunting of those contradictions you’ve all named so well, Matt, Vivek, Amy, and Meg. What I feel when I write, when I study poetry with the support of Canadian scholarships and citizenship that make such a risk possible, is a pang of doubt, something that arrives like a formal constraint: Are these words enough? And enough to do what, exactly? Enough to push past what feels like the welcomed register of critique? Doesn’t that just push the needle, extend the ouroboros? In my thesis, my main concern has been how poetics might help bring to light some of these contradictions implicit in the Canadian body politic that make holding solidaristic positions against these injustices we’ve been talking about more difficult—and here’s a section from a poem where I’ve felt this haunt:

“I am waiting for

Kurtis to tell me who to love

(when/and I am both so tired and young)

and the meaning of mottle.

I do have cigarettes for an Indigenous initiative, it turns out.

Do I know “cognitive dissonance”?

I look around. People

call this home when/and it isn’t.”

This haunting makes me move to destabilize, with language, the reverence of naturalized belonging in the nation-state. “When/and” represents settler belonging in both a temporal and conjunctive register, trying to create, in language, a moment in which something else is both possible and inevitable/unchanged. Is it ‘enough’? Probably not for the activist. But this feeling of wariness, of precarity—to have to hold under the knife all your work—this is how it feels for me to acknowledge that even my critiques of the Canadian nation-state are informed by, and, to some degree, sponsored by, the very values under critique.

NICK

What most interests me these days in terms of poetics is what is seen vs. what is not. What does the light of our poetry fall on? Sometimes I meditate on the opening lines of Christopher Dewdney’s poem “Radiant Inventory”, where he says: “The world has become / a spectacle of absence, / a radiant inventory. / The sunlight that falls on the margin of the lake / nurtures a deficit / in its clarity, its violence.”

When it comes to poems within our nation, I’m curious about that deficit of clarity. As we’ve all pointed to in one way or another, there is a tension in Canadian writing: a violent colonial state making a push to platform diverse and marginalized voices. Yet the entire process of publication requires a sort of consolidation, a streamlining, a fostering of a particular national image within the container of Canadian literature. What resolution is this image, then? What is being pulled into focus, and what isn’t? What are we not seeing? Does a deficit in clarity necessarily mean a deficit in violence?

Earlier last year, I wrote a poem called “Operation Soap”, about, as the title suggests, Operation Soap: a series of four bathhouse raids executed by Toronto police in February of 1981. The raided establishments were chiefly gay bathhouses. As explained in the poem, the men inside were:

“One-by-one, tagged and dragged out, then / pushed into the snowbank. A row of naked distinction / against the white of the streets. […] standing single file; a rogues’ gallery, / the crime being only what they do / in the showers, butting heads like rams.”

As recounted from oral histories in “Looking Back: The Bathhouse Raids in Toronto, 1981” by Nadia Guidotto, the men found inside were assaulted, arrested, called unrepeatable things, and marched into the early February snow outside for processing, most wearing only a towel. The justification for this was the enforcement of something called “common bawdy-house” law, a piece of sex work legislation that disallowed the operation of any place that facilitated “the practice of acts of indecency; (maison de débauche).” For those curious, “indecency” is never clearly defined. Therefore, by defining these bathhouses as “indecent” under the law, operating within a deficit of clarity, police were given the green light to commit a hate crime. The language of this section of the Canadian Criminal Code was maintained until its repeal in 2019.

This poem is my way of seeing, even if at a slant, what our country has done in better detail; writing in response to Canadian historical injustice, as Amy mentioned – my method of critique, my way of bringing further clarity into the deficit of what the sunlight of Canadian poetry falls on, to extend Dewdney’s wording. I think the question of whether the most radical act of writing “Canadian” poetry is to refuse to write it, as a way of refusing to let it be subsumed by the nation-state, is one worth posing. As Seamus Heaney asks in “Exposure”:

“How did I end up like this? […] As I sit weighing and weighing / My responsible tristia. / For what? For the ear? For the people? For what is said behind-backs?”

However, I think we have a responsibility to both ourselves as poets in Canada and to other artists elsewhere, not to silence ourselves as a method of protest or disavowal, but to instead further engage with our nation and its history – all parts of it, seen and unseen – in order to foster a more complete, well-rounded, detailed image of this country within the container of Canadian literature. I suppose I am also looking for something anadi, like Vivek, that can hold the entirety of “Canadian” experience and all its contradictions, past and present. But instead of looking for a wholly new container to house it in, I think we must expand this one by adding to it. As Slava said earlier, borders work to exclude and deny, but let’s not forget that they can also be redrawn. I believe this is the task. As Heaney puts at the end of Exposure, this is our “once-in-a-lifetime portent, / The comet’s pulsing rose.”

MATT

Perhaps it’s axiomatic that all poets, wittingly or unwittingly, address and are addressed by their nation-states in their poems. Where and how do you feel Canada talking to you, and perhaps through you in your poems? Where and how do you feel yourself addressing Canada?

TOSH

I’ve spent a large portion of my life feeling excluded from Canadianness in a way that I’ve come to understand as my lack of a white body. And I’ve spent an overlapping portion navigating how my complicity in the Canadian settler colonial project complicates those feelings.

When I think about Vivek’s question: “What borders are we writing from, as we write ‘Canadian’ poetry?” —I wonder whether sitting on these fence posts of belonging and exclusion might be some of the borders which make up my ‘Canadian’ poetry—where making sense of an exile or reconciling with a belonging exist as my poems’ shaping patterns.

In a poem I’ve called “Hockey Night”, the poem opens with the lines “It’s hockey night / in occupied / territory” —addressing again a tenuous contradiction of national belonging in Canada, and ends with a moment where the speaker is playing beer league ball hockey:

“But on the bench we don’t speak

we only swear

at the referees

and sometimes each other

and it makes me afraid

that I don’t know

how they know these plays.

Maybe that’s the origin of fear

wordlessness

the way knowing

hides in the body

and races out all

anger and shoulders

What men know

without knowing

keeps the country

cheering.”

I know this expression of “fear” —where the speaker doubts their cohesion to the group—is on one hand an experience of exile, a desire for belonging; and yet, I see it too as something that the speaker “know[s] without knowing”, a kind of belonging that “hides in the body” and “keeps the country”, an embodiment that generates its own fear—at wordlessness—and seeks for itself an exile.

JESSE

I can relate to a sense of exclusion from the boys and men that “know / without knowing” as you put it, Tosh, having always being the bullied for failing at my gender in these dynamics.

These fence posts of ‘belonging’ and ‘exclusion’ feel indicative of Canada’s place in my work as well. These themes often exist at a soft boil beneath & between my lines, but a poem that calls them to the forefront is Scotch Broom. In it, I speak to how my father’s side of the family came to be in Canada:

Elsewhere in this piece, I speak to my lack of knowledge concerning the Lekwungen names of plants I see while running at swan lake in Victoria where I lived for eight years, as well as to my experience of living in Japan and my inability to find a sense of belonging there due to my lack of a personal historical connection to that place.

This brings to mind something the poet Tim Lilburn did in his classes: Tim would offer a Canadian $100 bill to anyone who could name a local plant. Hands would shoot up but quickly dwindle when Tim clarified: the Indigenous name. For many years I held a desire to live outside of Canada, to be a ‘global citizen’ bouncing from country to country serving as a teacher of English as a foreign language; this quickly collapsed: this collapse is articulated in my poem Origami Crane: Aflame:

You’re right, Matt, it is axiomatic that all poets, wittingly or unwittingly, address and are addressed by their nation-states in their poems. We address and are addressed by Canada on a continuous basis, not to mention, as Amy does, that we receive privileged funding from granting bodies like the Canada Council for the Arts and the BC Arts Council, to which I will be submitting an application shortly.

Tosh, Meg, and I were having a conversation a few weekends past about how wealth privileges those who would like to live privately, away from other people to remove themselves from discourse(s) as best as they’re able: as a poet, specifically a Canadian poet, I don’t believe I can afford this option, the liminal space of my settler colonial status shouldn’t be escaped.

I think my work should take up a responsibility to hold Canada to its claimed objective of reconciliation to some degree: steer the state toward a dissolution of itself to have any hope in forming a more supportive situation for its ‘subjects’. This may be a job of Canadian poetry; I hope to see and be a part of such a communal, post-colonial literary culture.

SLAVA

I feel addressed by a variety of states. Being in Canada has at once increased my sense of alienation from the State of Israel and helped me feel more at home in Hebrew culture by allowing new context for its usage. Canada speaks to me and through me using the English language, but English has been as much a loss, as an acquisition.

Coming to Canada has felt like a return, and like a more acute phase of exile. I feel called by the English language here and called away from it by others. Sharing Jesse’s fascination with world cultures, I feel the need to weave together multiple worlds, to suggest an intermediate one. On one of my prose poems, when I look at a local tree, I see anything but the tree: