Christian Bök has graciously allowed us here at The Woodlot to publish an excerpt from his upcoming conceptual text My Works, Ye Mighty. A follow up to The Xenotext, My Works, Ye Mighty contemplates two vital concepts in literature: longevity and scale. In the opening, titular poem, Bök meditates on the impermanence of human activities and culture juxtaposed next to the almost universal desire to leave an immortal legacy. In the accompanying essay, “A Zoom Lens for The Future of The Text” he contemplates poetry of scale—what constitutes the smallest and largest meaningful unit of poetry, where those limits have existed throughout time and medium, and importantly, if those limits still exist with the aid of today’s technology.

Here is an excerpt from My Works, Ye Mighty as both a slideshow and in essay form below:

01.

Conceptualists have distinguished themselves as poets in part because they explore what I call the “limit-cases” of writing, taking an interest in the most marginal extremes of expression. Some of us, for example, have investigated the limit-cases of “scale” in poetics, composing poems not only as puny as molecules of sugar at the atomistic scale of our DNA, but also as vast as databases of email at the archivist scale of the National Security Agency (NSA).[1] Even though “scale,” as a value, has received only the merest notice in the history of poetics, I believe that a sense of scale (be it in degree, in volume, in length) remains crucial to us if we wish to understand the fundamental perspective of poets, who must often adopt a position with respect to their own “unit” of composition — a unit that, whatever its scale, must act like an “atom,” recopied and adjoined to make a text.

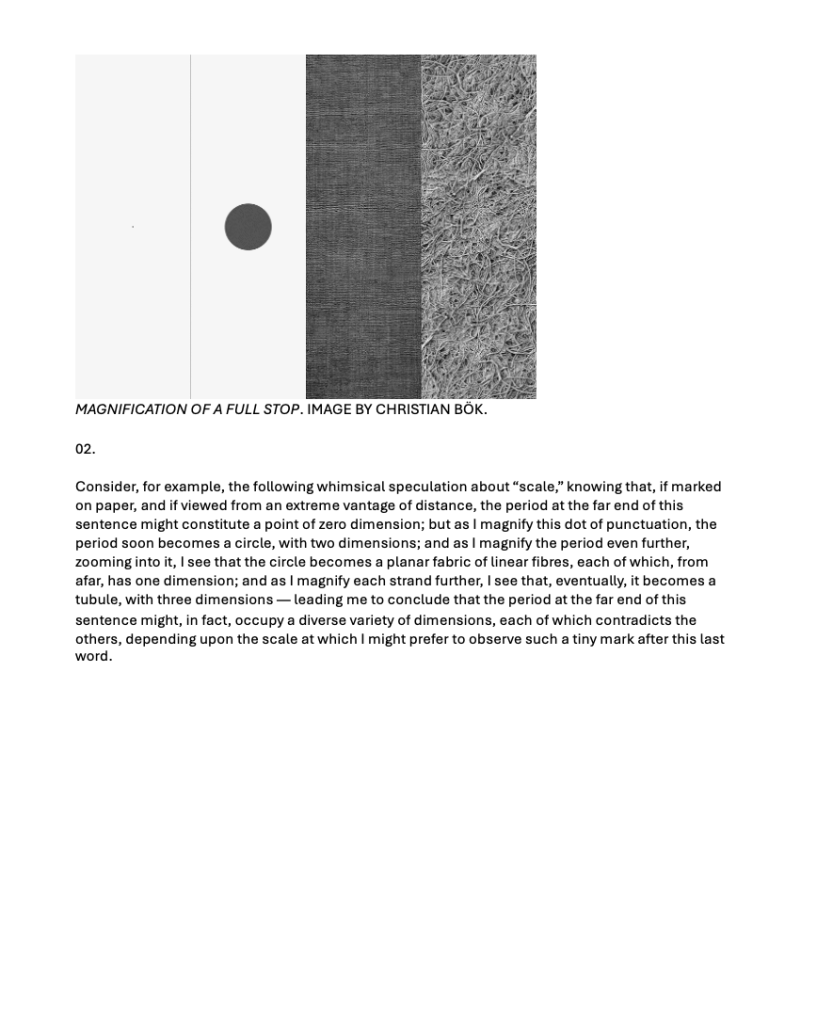

02.

Consider, for example, the following whimsical speculation about “scale,” knowing that, if marked on paper, and if viewed from an extreme vantage of distance, the period at the far end of this sentence might constitute a point of zero dimension; but as I magnify this dot of punctuation, the period soon becomes a circle, with two dimensions; and as I magnify the period even further, zooming into it, I see that the circle becomes a planar fabric of linear fibres, each of which, from afar, has one dimension; and as I magnify each strand further, I see that, eventually, it becomes a tubule, with three dimensions — leading me to conclude that the period at the far end of this sentence might, in fact, occupy a diverse variety of dimensions, each of which contradicts the others, depending upon the scale at which I might prefer to observe such a tiny mark after this last word.

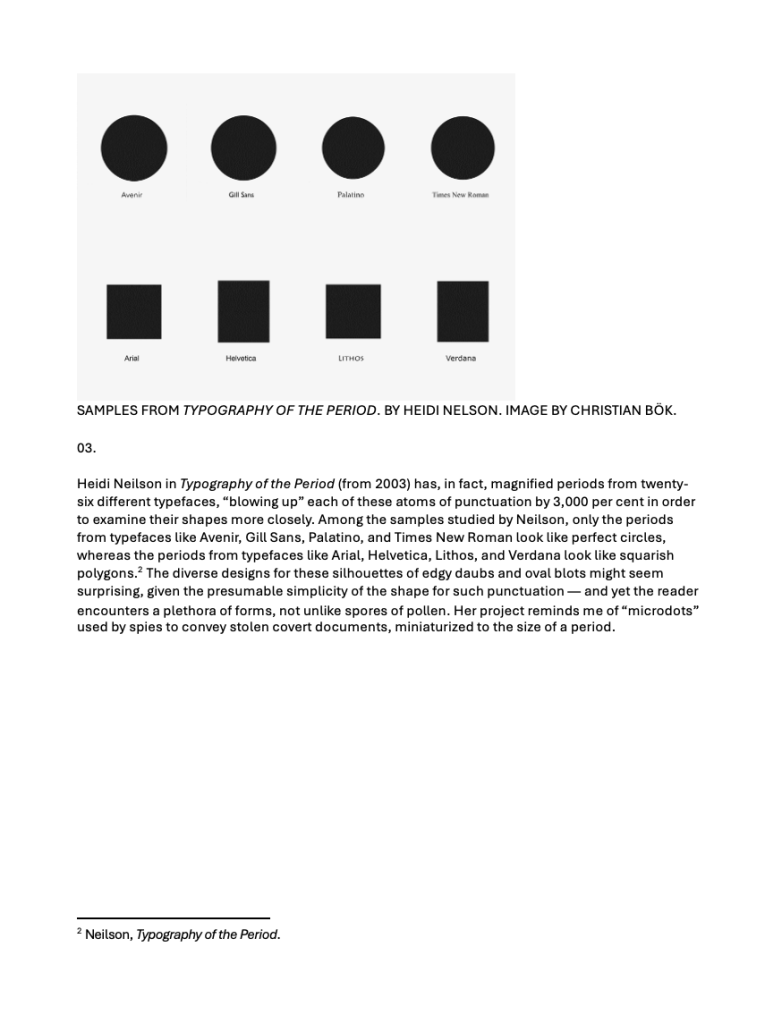

03.

Heidi Neilson in Typography of the Period (from 2003) has, in fact, magnified periods from twenty-six different typefaces, “blowing up” each of these atoms of punctuation by 3,000 per cent in order to examine their shapes more closely. Among the samples studied by Neilson, only the periods from typefaces like Avenir, Gill Sans, Palatino, and Times New Roman look like perfect circles, whereas the periods from typefaces like Arial, Helvetica, Lithos, and Verdana look like squarish polygons.[2] The diverse designs for these silhouettes of edgy daubs and oval blots might seem surprising, given the presumable simplicity of the shape for such punctuation — and yet the reader encounters a plethora of forms, not unlike spores of pollen. Her project reminds me of “microdots” used by spies to convey stolen covert documents, miniaturized to the size of a period.

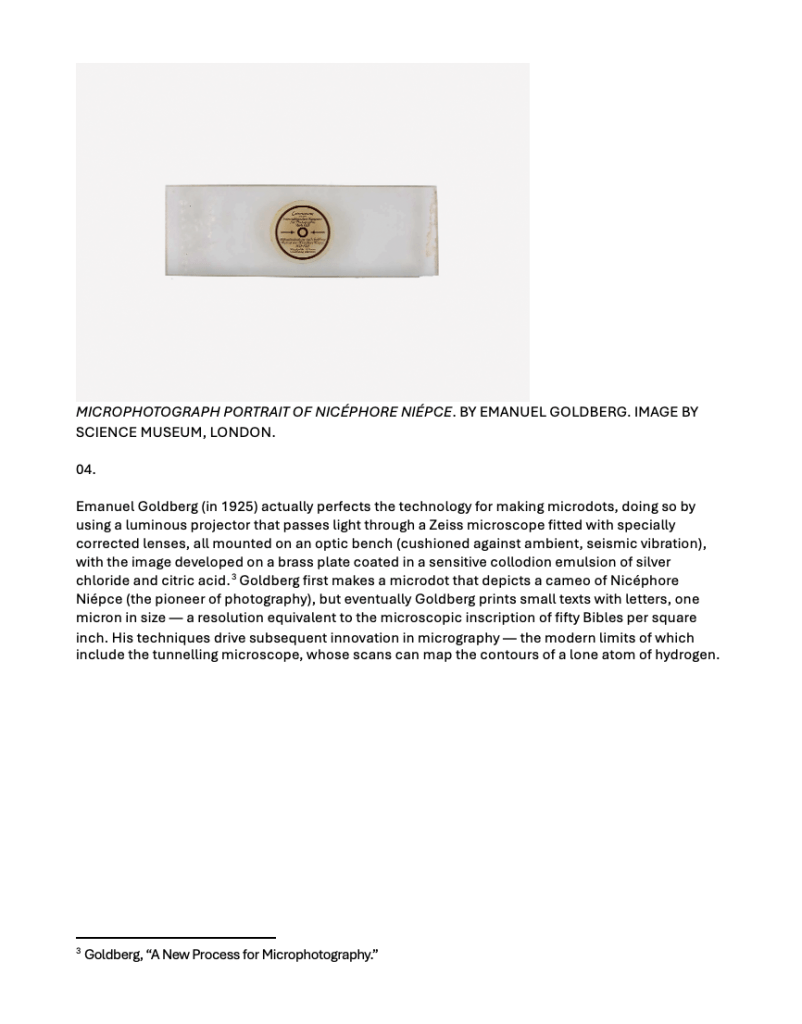

04.

Emanuel Goldberg (in 1925) actually perfects the technology for making microdots, doing so by using a luminous projector that passes light through a Zeiss microscope fitted with specially corrected lenses, all mounted on an optic bench (cushioned against ambient, seismic vibration), with the image developed on a brass plate coated in a sensitive collodion emulsion of silver chloride and citric acid.[3] Goldberg first makes a microdot that depicts a cameo of Nicéphore Niépce (the pioneer of photography), but eventually Goldberg prints small texts with letters, one micron in size — a resolution equivalent to the microscopic inscription of fifty Bibles per square inch. His techniques drive subsequent innovation in micrography — the modern limits of which include the tunnelling microscope, whose scans can map the contours of a lone atom of hydrogen.

05.

Don Eigler at IBM (in 1989) deploys such a tunnelling microscope to position thirty-five atoms of xenon on a plate of cooled nickel so that, by spelling out the trigram for the company, these dots of matter actually comprise the smallest artifact so far manufactured by humanity.[4] Eigler has gone on to draw the kanji glyph for the word atom by arranging atomic pixels of iron on a sheet of cooled copper; moreover, he has arrayed molecules of carbon monoxide on a metal panel, so as to write a waggish comment, measurable in nanometres: “If you can read this, you are too close.”[5] Such techniques of microscopic inscription (using the tiniest of all periods) has given IBM the power to store one bit of digitizable information in no more than a dozen atoms at a time, thereby increasing the possible capacity for storage of data upon the metallic surfaces of microchips.

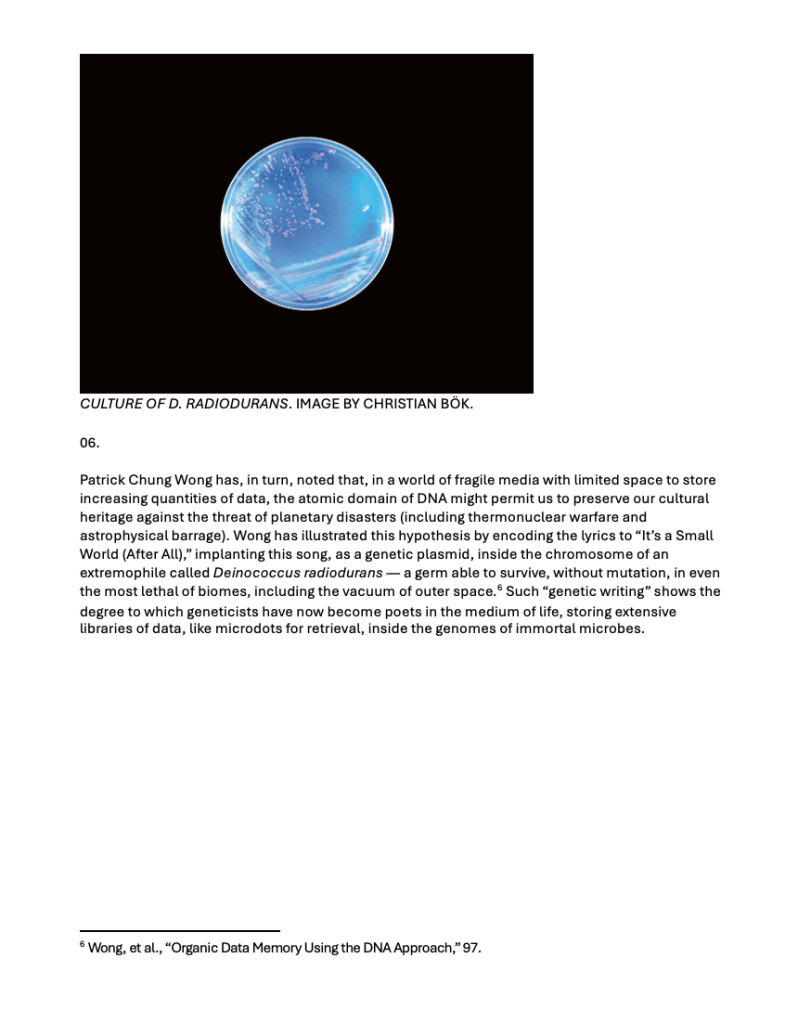

06.

Patrick Chung Wong has, in turn, noted that, in a world of fragile media with limited space to store increasing quantities of data, the atomic domain of DNA might permit us to preserve our cultural heritage against the threat of planetary disasters (including thermonuclear warfare and astrophysical barrage). Wong has illustrated this hypothesis by encoding the lyrics to “It’s a Small World (After All),” implanting this song, as a genetic plasmid, inside the chromosome of an extremophile called Deinococcus radiodurans — a germ able to survive, without mutation, in even the most lethal of biomes, including the vacuum of outer space.[6] Such “genetic writing” shows the degree to which geneticists have now become poets in the medium of life, storing extensive libraries of data, like microdots for retrieval, inside the genomes of immortal microbes.

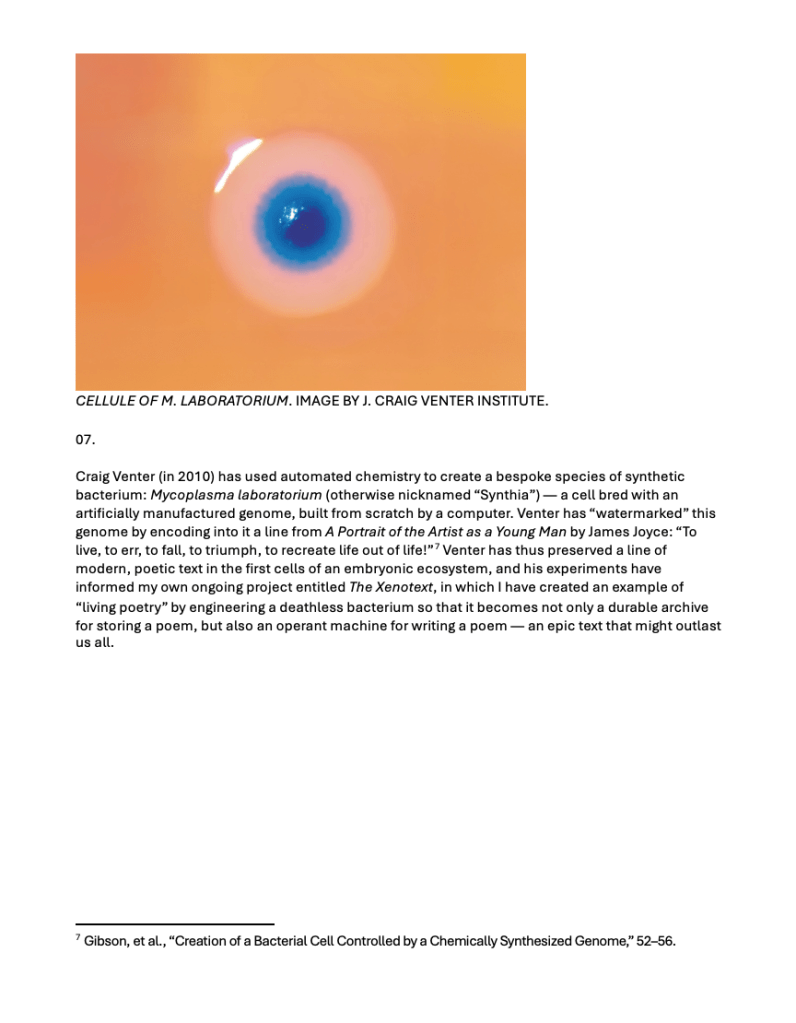

07.

Craig Venter (in 2010) has used automated chemistry to create a bespoke species of synthetic bacterium: Mycoplasma laboratorium (otherwise nicknamed “Synthia”) — a cell bred with an artificially manufactured genome, built from scratch by a computer. Venter has “watermarked” this genome by encoding into it a line from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce: “To live, to err, to fall, to triumph, to recreate life out of life!”[7] Venter has thus preserved a line of modern, poetic text in the first cells of an embryonic ecosystem, and his experiments have informed my own ongoing project entitled The Xenotext, in which I have created an example of “living poetry” by engineering a deathless bacterium so that it becomes not only a durable archive for storing a poem, but also an operant machine for writing a poem — an epic text that might outlast us all.

08.

Conceptualism must delve into this kind of molecular substrate for poetry, taking a cue, perhaps, from a poem like “Fact” by Craig Dworkin (who lists, exhaustively, all the chemicals in the very page of inked paper used to document the list itself — so that, in fact, the poem “Fact” must vary with each instantiation, since the constituents in the brands of inked paper change from publisher to publisher).[8] I might note that, despite the myopia of critics who feel obliged to dismiss the merits of such outlandish literature, the act of addressing this atomic degree of expression nevertheless constitutes one of the outlying horizons for the future of poetry. I believe that the acuity of our “vision” in poetry depends, in part, upon our ability to “zoom” across a multitude of unexplored dimensions, focusing upon each of them before ever reaching the finality of a full stop.

[1] The Xenotext by Christian Bök encodes a poem as a tiny gene inserted into the chromosome of a bacterium (E. coli), whereas The Hillary Clinton Emails (an exhibition by Kenneth Goldsmith) reprints the tranche of letters withheld by Hillary Clinton but released by WikiLeaks during the American election of 2016.

[2] Neilson, Typography of the Period.

[3] Goldberg, “A New Process for Microphotography.”

[4] Browne, “Two Researchers Spell ‘IBM,’ Atom by Atom.”

[5] Ganapati, “Twenty Years of Moving Atoms, One by One.”

[6] Wong, et al., “Organic Data Memory Using the DNA Approach,” 97.

[7] Gibson, et al., “Creation of a Bacterial Cell Controlled by a Chemically Synthesized Genome,” 52–56.

[8] Dworkin, “Fact.”