By Chris Banks

“Poetry is free but will cost you everything. The body is free but will cost you everything plus itself.” The riptide, I believe, in the poetry collection In A Riptide by Ronna Bloom, out this Fall with Brick Books, is the metaphysical and philosophical undertones in Bloom’s poems that are direct, concise; intimate and universal; and reverent of the deep image. In the opening poem “Immeasurable”, the poet Bloom introduces the four people who the Buddha meets during his travels which then become the various sections of the collection: sick person, old person, dead person, and happy person with nothing.

In part one “To Show The Scars: sick person”, the poet speaks of a tumour and a cancer illness treating such disclosure with honesty and a searching vulnerability that admits doubt and confusion and fear and even hope in lines like, “keep staring at the blue sky like it’s your pain, / eventually it will change colour.” The diction of Bloom’s poems is conversational at times, and at other times, she gleefully drops in serious word-play like “gut-sharked”, “simped-out”, and “my vibrato, my fascia, my organs, my aura.” But it was really what Bloom does with imagery that really stood out to me as I read In A Riptide for beneath “A death bucket of news” and “anyone can be a dictionary of myths” there are new associations, swirling, and new meanings to be found.

Take for instance this line “An x-rayed tumour on a spine / looks like a wad of gum on a radial tire” with its simplicity of language and direct everyday association with chewing gum, and still there is some lucid, deeply compassionate, and spiritual resonance beneath that line.

I also enjoyed all the allusions in the collection, everyone from Carl Jung, to Rilke, to Francis Bacon, to Charles Bukowski and Emily Dickinson. Yet it is the imagery again that gave me the most pleasure, and ignited the most envy in me like in Bloom’s poem “Today in the street”:

The second line “Their faces are occupied the way a country is” is a perfect, perfect line which implies the hidden resentments, or hopes, or memories, or illnesses, that pull a self under while only a mere hint of that undertow, those vexing thoughts, appearing on the surface of our faces while we pass strangers in the street. The next stanza suggests almost the erasure of the speaker’s self with its reference to the wind moving to a place I’m not in, or maybe its more of a metaphorical wind where societal problems exist everywhere outside of a person. The line “My gratitude for the cup doesn’t fill the cup” suggests the desire for happiness, or desire being at odds with gratitude. The ending too is lovely with its implied metaphor that we are all stunt people crashing through our lives filled with our own difficult, death-defying scenes.

It is lines like the ones excerpted above, and others throughout the collection, lines like “Take in / a slow breath to know the air / within you is also around you.” and “The past is everyone’s / ghost horse, and it keeps breathing as it carries us”, and “Love appears unexpectedly…. / …. like a mountain after months of fog” that really swept me up, and had me rereading the collection several times. Another lovely passage is from “Five Elegies” in the third section “The Earth Held Me: dead person” which is intimate, conversational, plain-spoken but also elegiac and deeply archetypal:

Those last two lines are full of resonance and expand the poem into archetypal territory as death and grieving and bearing witness are all part of our collective human experience. Bloom has another terrific short poem called “Afterward” that is a real treasure and takes up the same themes:

I’m not sure how to read this poem for the speaker is suggesting either the loss of a loved one is palpable but mostly unseen, or else it implies when one dies that is the end of it. There is nothing left to be done. No one left to talk to. Nothing. Honestly, those lines “Death leaves you so alone. / Your hand goes through a mime’s window” are some of the best lines in the collection.

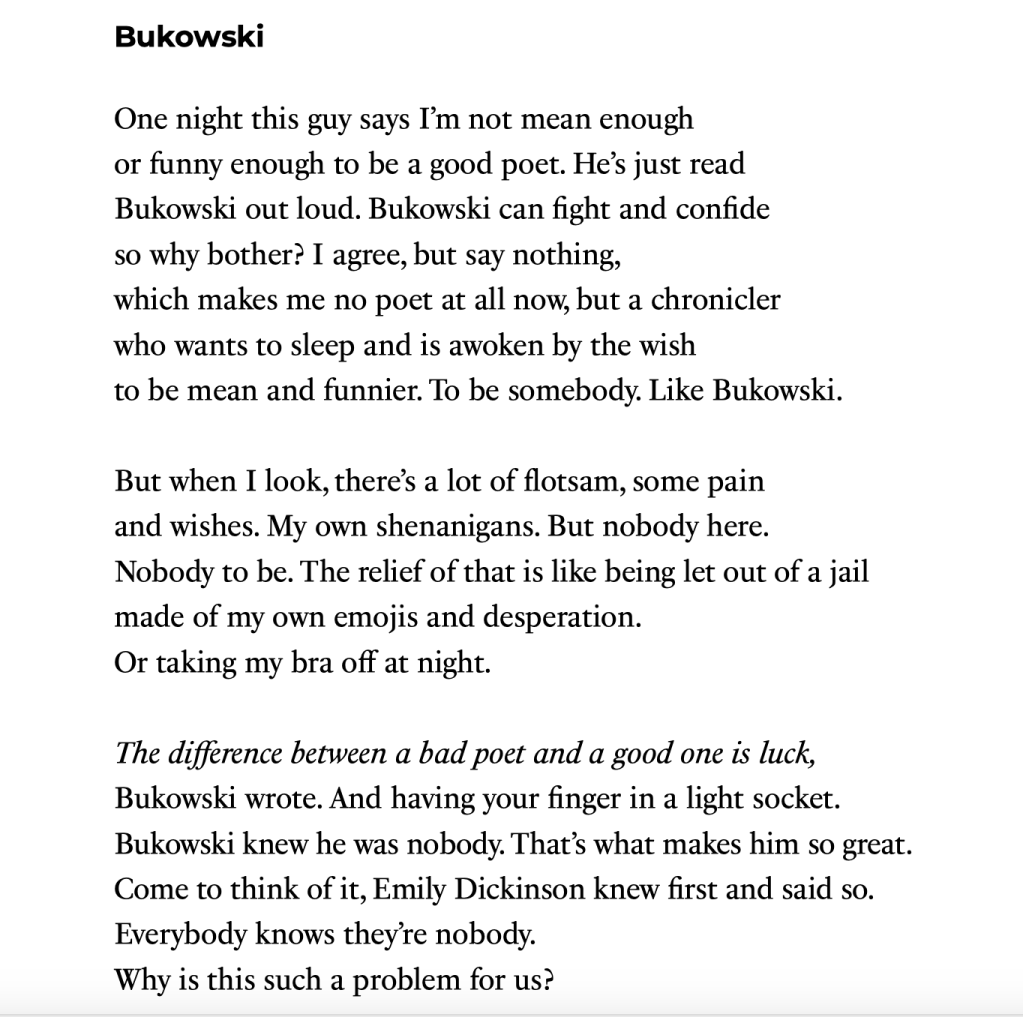

Finally, in the last section of the book “Don’t Close The Door To The Door To The Door: happy person with nothing”, the poet comes to a place of contentment and solace by not attaching to worldly things, or pressing worries, and this is really felt in the poem “Bukowski”:

I like the lyric personal voice used in this poem which really makes me feel both empathy and a little “cringey” as we have all been that poet at the party where someone on finding out we write poems tells us that they loved Bukowski in college. But even here, Bukowski transcends his hard-scrabble, dirty old man persona, and comes to represent the Buddhist notion of anattā, or unself, as the self, even Bukowski’s barfly poet celebrity, are illusions, and non-attachment–especially to desire and to other fleeting feelings–is what brings personal liberation or contentment, even for poets.

In A Riptide by Ronna Bloom is a wonderful book out this Fall with Brick books. The poet Ronna Bloom employs a direct, conversational, deceptively “simple” tone in her poems, but the images themselves are anything but simple: koan-like, riddling, surprising, and exact. I think any reader of Canadian poetry will recognize the strengths of Bloom’s enigmatic imagery and her intimate, personal voice in In A Riptide, and be both pulled into its undercurrents and swept out into its larger themes which is really all any poet can hope for.

Chris Banks is an award-winning, Pushcart-nominated Canadian poet and author of seven collections of poems, most recently Alternator with Nightwood Editions (Fall 2023). His first full-length collection, Bonfires, was awarded the Jack Chalmers Award for poetry by the Canadian Authors’ Association in 2004. Bonfires was also a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award for best first book of poetry in Canada. His poetry has appeared in The New Quarterly, Arc Magazine, The Antigonish Review, Event, The Malahat Review, The Walrus, American Poetry Journal, The Glacier, Best American Poetry (blog), Prism International, among other publications. Chris was an associate editor with The New Quarterly, and is Editor in Chief of The Woodlot – A Canadian Poetry Reviews & Essays website. He lives with dual disorders–chronic major depression and generalized anxiety disorder– and writes in Kitchener, Ontario.