by Chris Banks

The Canadian Long Poem is having a bit of a renaissance right now. Everywhere I look, I see Canadian poets churning out verse novels, or book length poems on everything from climate change to lesser known historical figures, or poetry sequences that feel like long poems, or powerful 10 page long-winded poems meant to balance out the more concentrated shorter lyrics in carefully curated collections.

My question is, what makes a long poem successful? I remember being a young man and picking up a copy of The New Long Poem Anthology 2nd Edition, and being puzzled and feeling a little adrift by some of the poems chosen. I really loved “No Language Is Neutral” by Dionne Brand I remember, and I’ve always enjoyed Phyllis Webb’s poetry after seeing her read at the University of Guelph in 1990 so I really liked her “Naked Poems”, and of course there was Christopher Dewdney who I stubbornly loved, even though I was never really sure what he was up to.

I guess I found many of the poems in the anthology too different from the poetry I had grown accustomed to when I thought about Canadian Poetry. Canadian poetry was full of shorter personal lyrics with deep vatic images, or stuffed with page-length meditations on a rural childhood, or tight-lined exploratory poems about race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation. These types of poems have only proliferated since the aughts.

Those types of poems I understood, but the long poem was a different beast, one I longed to tame, but I eventually gave up because a long poem puts demands on a reader that my education, and probably my attention span too, were not up to the task of participating in at that time in my life. For me, I always read collections of poems at random, starting sometimes at the back, or in the middle, or thumbing through pages until a title or a first line hit just right.

One does not really do that with the long poem, I think. The long poem puts demands on a reader, and “the form” it chooses is one of its own design. We cannot rely on the familiar signposts of shorter lyric narrative poems, or the long epic poetry of yesteryear.

As Dana Gioia has stated in his essay “The Dilemma of The Long Poem”, “the long modern poem is virtually doomed to failure by its own ground rules. Any extended work needs a strong overall form to guide both the poet in creating it and the reader in understanding it. By rejecting the traditional epic structures of narrative (as in Virgil) and didactic exposition (as in Lucretius), the modern author has been thrown almost entirely on his own resources. He must not only try to synthesize the complexity of his culture into one poem, he must also create the form of his discourse as he goes along. It is as if a physicist were asked to make a major new discovery in quantum mechanics but prevented from using any of the established methodologies in arriving at it” (25).

I guess this is why it is hard to talk about what makes a long poem successful, because any poet who undertakes a long poem kind of makes it up as you go along. That is both the sources of its power, and its own weakness. The long poem is not concerned with utility; is this working or not?

I think the poet who writes the long poem is stepping out beyond the safety of orthodoxy, and is stretching out their poetic imagination, and asking, what lies beyond the safety of the short lyric? In essence, I think the long poem is a reaction against contemporary poetry aesthetics, and is looking to create something new, something hybrid, something at the very least different, and hopefully quite wonderful.

Whether a long poem is successful or not really depends on the reader as much as the writer. Is the reader up to the demands the long poem places upon her? I admit I like to read poems in snatches of stolen time, so it is hard for me to sit with a long poem and to read one start to finish. Often, long poems are playing with structure, with lines rivering all over the page from left to right, or maybe they have two different “voices” amplified side by side on a page, or they position one short passage in large font alone on a page, or conversely, the very next page is a dense accumulation of historical documentation and adroit imagery.

What I’m saying is the long poem is in it for the long haul; readers not necessarily so much. So why write the long poem if the chance of failure, or being misunderstood, or–gasp– maybe not read all the way through is so high?

Well, I think there is a particular kind of poet again who is bored by writing the same small poems, year after year, and they hunger to do something different. They want to put one over on the reader, or try something new, and there is something really liberating about working on a piece where the usual gold standard poetry detectors are rendered a little useless, and readers have to rely on their own eyes and ears.

Remember, poetry originated as a form of vocal music, and I think the long poem is really harkening back to a time when poetry was meant to be heard as much as read. It opens the front door, and airs out the short poem (looking as it does obsessively for that “inevitability of phrasing” Harold Bloom equated with all great poetry), and just says to the poet writing it: go for it.

When I think of the Canadian Long Poem, I think you have to talk about Jason Guriel’s Forgotten Work, a long verse novel composed of 216 pages of iambic pentameter couplets, as the sheer ambition required to undertake such a book is extraordinary. The book combines Guriel’s love of speculative fiction and music and poetry and Peter Van Toorn’s landmark poetry collection Mountain Tea. Verse novels feel impossible to me, especially after I read Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate (a book written in 590 perfect sonnets about San Francisco in the 1980s), so I am envious and, in awe really, of poets like Guriel who can really pull it off.

Other recent Canadian verse novels are Yvonne Blomer’s Death Of Persephone: A Murder, a skillful reimagining of the Persephone myth with its polyphony of voices and characters, and Daniel Cowper’s Kingdom of the Clock set in a coastal modern city with eccentric characters and vivid imagery. Although not a long poem, per se, Paul Vermeersch’s latest collection NMLCT out with ECW Press this Fall feels like a long poetry sequence, and has narrative elements. Then there is Shane Neilson’s The Reign which I am currently reading. It is a book-length fairy-tale about New Brunswick centering on an intellectually disabled man named Willard, and through 14 sections readers hear the voice of Willard, and the forest, and even the poet. So far, the section that is entitled “The Forest Speaks” is my favourite because it overwhelms the reader with its long lines and its many allusions and quizzical rhetorical questions.

Just in the last month, I have read and enjoyed Stephanie Bolster’s latest book length poem Long Exposure which felt like a long ceremony of witnessing as the poet looks at the various environmental crises humans have faced in the last hundred years; and meditates on the photography by Robert Polidori who took devastating photographs of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. And even Robyn Sarah’s latest collection We’re Somewhere Else Now has a powerful long poem sequence called “In The Wilderness: A Soliloquy in broken time”, which takes on the subject of time passing, doubt, God, and other big life nagging questions.

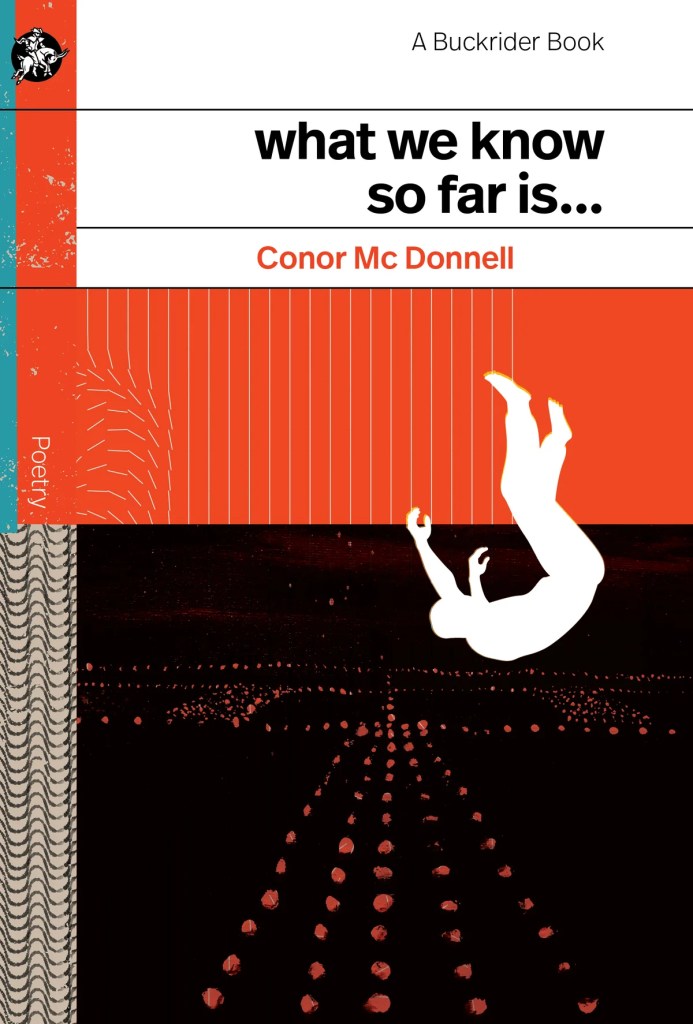

There are Canadian poets who have attempted the epic poem for the sheer exuberance of it. Marc Di Saverio wrote his Crito Di Volta published with Guernica Editions in 2020, and this season’s what we know so far is… by Conor Mc Donnell takes up the long epic form using cinematic language. I had the pleasure of reading this book ahead of time and blurbed it saying, “This long poem is equally concerned with thought and feeling, with biology and memes, with the murmuration of birds and the susurration of words we whisper silently to ourselves but that we wish for others to hear.” It’s an ambitious book for those willing to sit with it, and to let its meaning-making work upon the reader.

So I guess the long poem in Canada is having its moment, or maybe its always been there, and I’ve been too busy writing my own small lyric poems, or my lightly surreal slapstick meditations on Death, to notice. But I do think, the various poets writing the long poem in an array of forms and styles are exploring what lies beyond contemporary mainstream poetics. I think that is something to be celebrated, even if the books themselves present challenges and difficulties that a short minimalist narrative poem does not.

I like all kinds of poetry, but I am more comfortable evaluating shorter lyrics simply because I have read so many more of them. What makes a long poem successful? I think ultimately readers make that decision, but I like that there are poetic outliers writing long form poems out there. In my next book, I have one long six page poem about the Canadian national identity, or lack of it, and writing that I felt absolutely emptied and winded. Will I attempt a long poem in the future?

Honestly, I am not sure, but I think it is terrific that there is a diversity of poetic approaches to match the vast diversity of poetic voices in Canada. It speaks to the health of our literature, but also to our suspicion of too much poetic orthodoxy, too much sameness in our poems. The long poem feels mischievous, nonconformist, part hell-raiser, part oracle, and the poet who writes them a kind of modern contemporary apostate challenging not only our notions of what poetry is, but ultimately can be.

Chris Banks is an award-winning, Pushcart-nominated Canadian poet and author of seven collections of poems, most recently Alternator with Nightwood Editions (Fall 2023). His first full-length collection, Bonfires, was awarded the Jack Chalmers Award for poetry by the Canadian Authors’ Association in 2004. Bonfires was also a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award for best first book of poetry in Canada. His poetry has appeared in The New Quarterly, Arc Magazine, The Antigonish Review, Event, The Malahat Review, The Walrus, American Poetry Journal, The Glacier, Best American Poetry (blog), Prism International, among other publications. Chris was an associate editor with The New Quarterly, and is Editor in Chief of The Woodlot – A Canadian Poetry Reviews & Essays website. He lives with dual disorders–chronic major depression and generalized anxiety disorder– and writes in Kitchener, Ontario.