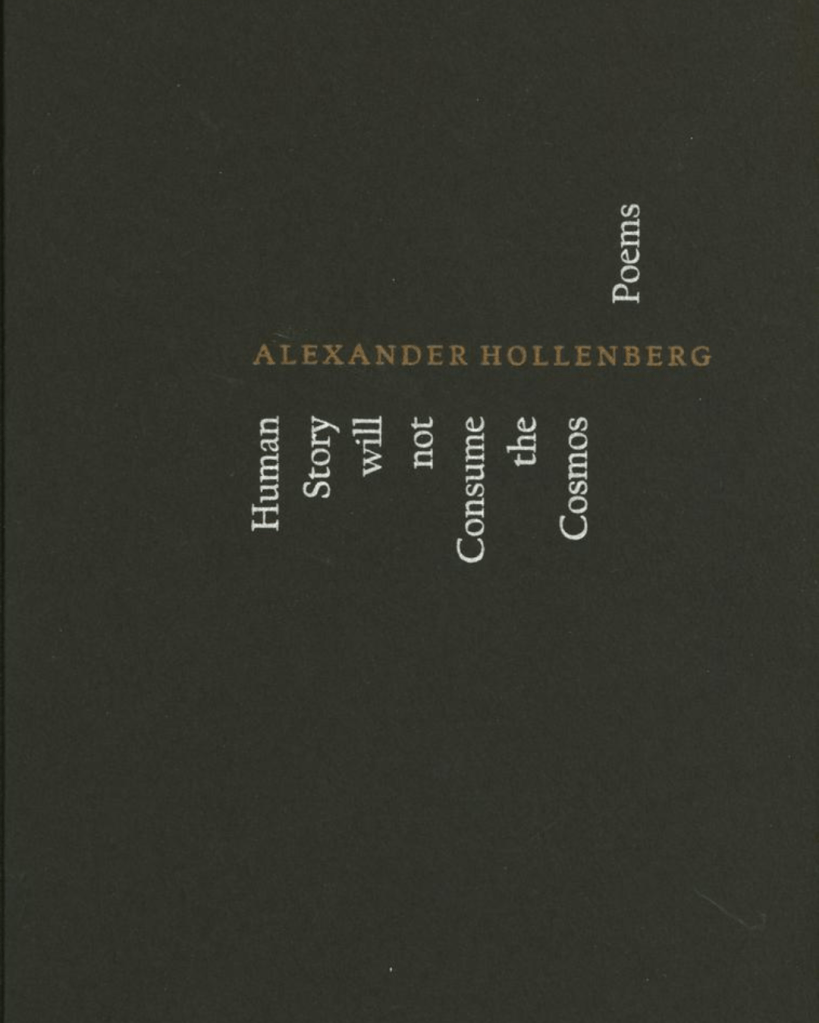

Interviewer Wren Ashenhurst talks with Canadian poet Alexander Hollenberg about his poetry collection Human Story Will Not Consume the Cosmos (great title!), out with Gaspereau Press!

‘Wren Ashenhurst: Congratulations on your debut poetry collection, Human Story Will Not Consume the Cosmos. I’d like to start with one of my favourite poems, “The Stair Lift.” In it, you write, “Your heart was gone before we met/broken unpoetically—” I love that idea in particular, “broken unpoetically,” then trying to fit it into a poem. For you, where does the distinction between something being poetic or unpoetic lie?

Alexander Hollenberg: That’s a great question. What makes poetry such a special, necessary discourse is its quality of attention. Anything—any subject, any experience—can become the stuff of poetry with the right words and the right touch from the right poet. That said, I know we feel it in our bones and see it on our screens and in the daily vicissitudes of modern life that there’s so much of this world that is unpoetic. And I don’t mean to say the distinction is one of beauty versus ugliness, or anything so crude; rather, what I’m trying to get at in “The Stair Lift” is that the broken heart—literally, the moment of cardiac arrest—is unpoetic because it lacks rhythm. That’s the conceit there. So maybe the distinction between the poetic and unpoetic is the distinction between life and lifelessness, the difference between the electric thrum of embodied imagination versus the ready-made, ersatz language of chatbots and their defenders. (“I sing the body electric,” writes Whitman!) I want to say, too, that in some moments, some things are just too difficult to write about. The everyday world intrudes on our best efforts to make art, to pay attention, to find new rhythms and connections. But that paralysis—that nagging feeling that lifelessness is the new norm—that’s also the justification for more poetry.

WA: I’m interested in the structure you used in your book; it is broken into five named sections, each containing an epigraph. What were your thoughts behind dividing the sections this way, and how did the epigraphs come about?

AH: Though the book is made up of discrete sections, I see them more as woven together, rather than standalone. It’s a recursive collection—words, images, and phrases repeat throughout the text and fold back in on themselves, suggesting, I hope, the ways stories build upon themselves and are constituted through a variety of human and non-human ecosystems. The first section, “Spruce Crow,” considers how non-human agents and spaces—a crow, a shoot of wild raspberry, the entire pre-Cambrian shield, for instance—resist discourses of human belonging. The second section, “Cod Jigging near Twillingate,” thinks hard about how anthropocentric thinking may painfully and provocatively blur the line between love and violence. “Children of Atlantis,” shifts the focus and asks repeatedly what it means to feel nostalgic for spaces and places to which we never belonged in the first place. The penultimate section, “The Human/it/(y)/(ies),” celebrates the humanities’ capacity for creative, interventionist thinking, while also explores the nonhumanity of the institutions built around them. The final section, “Human Story will not Consume the Cosmos, or, Thirty Ways of Looking at the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART)” tries to bring all these ideas together through the conceit of humanity’s attempt to redirect an asteroid, as practice for the apocalypse. As you mentioned, each of these sections is introduced with a little epigraph, taken from one of its poems. I like a good epigraph—it’s kind of an amuse-bouche for the reader, isn’t it? Preparing them, teasing them, hopefully getting them eager for the main course. But also, maybe because so much of the book is about the responsibility of stories and storytellers, the act of dislocating these little pieces of language into new contexts was just another attempt to explore the slippery, wriggling life born of every utterance.

WA: That’s interesting, I noticed that in the book’s early sections, your poems lean very heavily on nature and natural images. In the section “Cod Jigging Near Twillingate” you’ve written about fish and fishing. Do you fish yourself? How did you get into it?

AH: I suppose my background in fishing isn’t all that unique, descending from my father and grandfather, who for two weeks every summer in Quebec would wake me and my brother up at 5:00am, plunk us in the boat with them and spend the next three hours waiting for something to happen. Usually nothing happened. None of us were very good fishermen, and by the time I came around, the lakes were emptier—many of the species my grandfather reminisced about (speckled trout, ouananiche, muskie) just weren’t there anymore. But, of course, as most anglers will tell you, the waiting’s the thing. The being out-there-on-the-water under a big sky, tracking spruce trees on the shore, watching your line crease the water, the soft wake of the boat, the being-quiet and being-alone, even when you’re with others. There’s not much to do other than pay sustained attention to things (and thoughts) that would likely pass you by on shore. Which is a pretty good early lesson in poetry. But there’s the other side of this too—all this beautiful waiting is also a waiting to do some sort of violence. The hooking of the fish, the fighting of the fish, the landing of the fish, the eating of the fish. You can’t escape that, and you can’t pretend fishing isn’t also that. If you think of fishing-as-story-structure, its narrative closure is always fraught, not-quite-satisfying. Maybe it’s that ambivalence that attracts me to fishing as a writing subject—the mixed ethics of quiet attention to and frenetic domination of the non-human world. I love that I can write love poems like “Cod Jigging near Twillingate” or “Surgeon’s Knot,” out of that type of experience, but man, it troubles me, too.

WA: Another one of my favourite poems in the collection comes from “Cod Jigging Near Twillingate.” “We Create Wavelengths First,” is such a playful poem, in which the speaker is taught guitar by Gordon Lightfoot in a dream. I was curious what your relationship with Gordon Lightfoot and his music was like at the time you wrote the poem? Did you find it changing after you wrote the poem?

AH: I wish I could say I had a relationship with Gordon Lightfoot! When I was maybe 14, I got it in my head that I would write Gordon a letter asking him to teach me guitar, and I was legitimately convinced he’d be so enamoured of my request that we’d become fast friends. Years later, I had a history professor use the opening lines of the great “Canadian Railroad Trilogy” to teach us about terra nullius—that colonialist rhetorical move of declaring an Indigenous space empty in order to dominate the land and its inhabitants. I wanted my poem to explore this tension—the deep, formative love that is built from the art (and artists) we admire against the deep, formative languages we inherit, which often expose us as flawed, myopic humans. I love Gordon Lightfoot’s music. It’s a masterclass in how to build out the relationship between lyric and storytelling. My poem’s dream narrative is a small attempt to honour the mythos he constructed over a lifetime of deliberate, creative work, even if every mythos, every word, every wavelength is always, ultimately, going to be an imperfect creation.

WA: Human Story Will Not Consume the Cosmos seems to struggle against the human instinct towards meaning making and story. As readers, we see this in your repetition of the concept of “human stories,” and a couple of the poems contain the phrase or concept to “become a little less human.” Where did this conflicted relationship with the human-centric come from and how did writing the collection develop your thoughts on it?

AH: You’re right—that phrase, “a little less human,” repeats several times throughout the book, kind of erupting into different contexts. I’m not sure I was so much struggling against the human capacity to make meaning, so much as struggling to find a way to live with it. Of course, we’re never going to stop telling stories: as soon as we choose to represent a happening, we’re making a claim upon our audience and also upon the world. And these are always, inherently, ethical claims—you should listen to this, there’s something that needs to be told, let me in for a moment. There’s real power in the act of telling. But how do you balance that power against a non-human world that doesn’t—recognizably—tell stories back to us? I’m thinking now of Robert MacFarlane’s spectacular book, Is a River Alive? Yes, a river is alive, and yes, we have a responsibility towards it, but it doesn’t “speak” in the same way we do, so what do we lose of the river when we inevitably represent it through the filters of human language and narrative? My book is worried about that, certainly. But I also hold great hope for the ethical power of story—even when we misrepresent, we have the opportunity to try again. The phrase “a little less human” isn’t, in this case, a wholesale deferral of power; it’s something more modest—can we try out being just a little bit less like ourselves for a time? I think of it as a small shift in our seats, a rethinking of our comfort in the world and how we talk about it.

WA: The titular poem, “Human Story Will Not Consume the Cosmos” ends the collection, isolated in its own self-titled section. The phrase speaks to a sort of ephemerality of the human story and human stories that I find very striking. Where did this phrase come from and how did it shape the development of the collection?

AH: The phrase first appears in an earlier poem, “Exile Happens as Soon as You Speak,” where I write “and maybe making the world paratactic/at least allows for the possibility/that human story will not consume the cosmos.” This was a poem I wrote while thinking about William James’s A Pluralistic Universe, where he uses the word ‘and’ as a centrepiece for his pragmatist, pluralist philosophy. James convinced me there’s something really special about ‘and’: it’s this beautiful little conjunction that brings things together but doesn’t impose any larger causation or interrelation between those things, unlike, say, ‘because’ or ‘but.’ In other words, it lets objects retain their singularity whilst being part of the same cosmos. When I wrote the book, I was trying to think this through. How do we tell stories and write poems about the non-human world without imposing ourselves on that otherness? There’s something really audacious about being human, isn’t there? We create, we build, we destroy, we make the world look and feel wholly different than it ever would without us, and yet, this is not just our world. Not even close. That last, long titular poem explores that audacity with a bit more clarity than the earlier ones. It’s about how we tell stories about the end of the world, using NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test as an extended metaphor for how we talk about saving (and ending) the world. It’s also a paratactic poem, built out of brief vignettes that both tease and refuse connection, suggesting real limits to the human capacity to make meaning out of non-human things. When I write that human story will not consume the cosmos, I’m suggesting that this planet has never, ever, been fully ours—that eventually the planet is going to exist without us and endure. But it’s also a plea for the now, part of an ever-growing, cacophonous, beautiful chorus of human voices—let’s find new stories and new ways of telling that better represent our responsibility to this pluralistic universe.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alexander Hollenberg is from Hamilton, Ontario. He is a Pushcart-nominated poet and professor of storytelling who loves to write about crows, fish, and the humanities. His debut collection, Human Story will not Consume the Cosmos, was published by Gaspereau Press in June 2025. Some of his new work can be found in Contemporary Verse 2, The Dalhousie Review, Arc Poetry, and The New Quarterly. He is a past winner of Contemporary Verse 2’s Two-Day Poem Contest.

Wren Ashenhurst is a queer trans/nonbinary writer from the Canadian west coast. Their poems can be found in Defunkt Magazine and forthcoming from Pulp Mag.