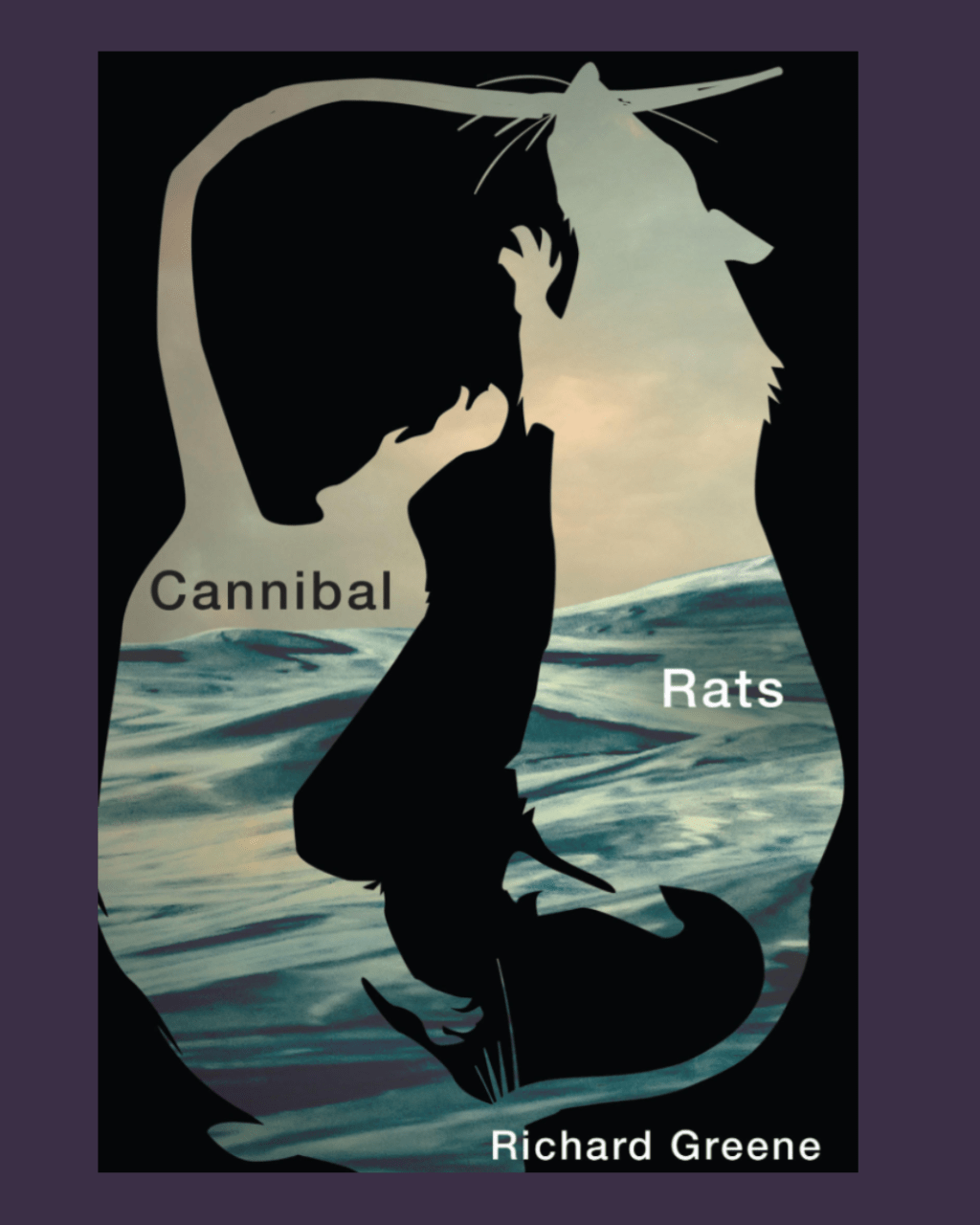

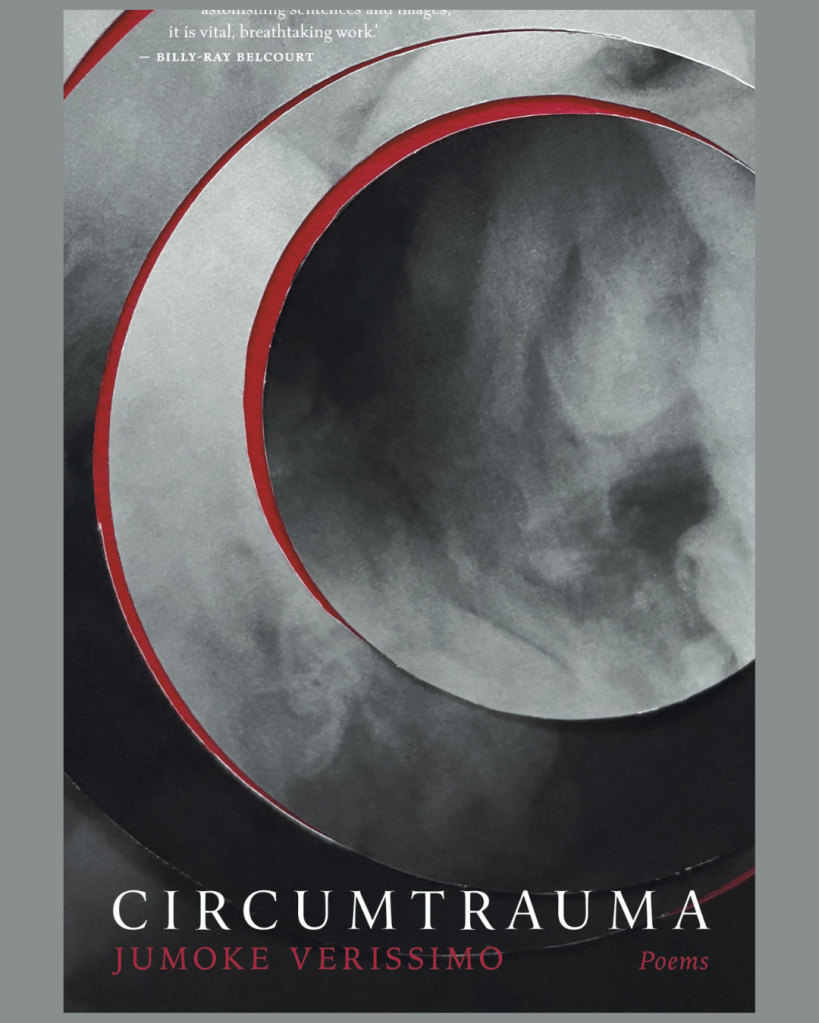

Interviewer Breanna MacElwain talks with Canadian poet Jumoke Verissimo about her poetry collection Circumtrauma (Coach House Books, 2025) for The Woodlot!

Breanna MacElwain: Congratulations on the publication of Circumtrauma. I’m hoping to have a poetry book published myself one day. I was really affected by the striking and visceral lines in your poems, such as “we all wanted to be shot” and “death came before the bullet.” How did your study of intergenerational trauma inspire the imagery in this book?

Jumoke Verissimo: Thanks a lot. I wish you nothing but success on your journey towards publishing a new book. The imagery in the book developed from my PhD research. It was an attempt to resist an echo of my own voice or to make the poems about my own reflections or re-observation (considering that I never witnessed that war, there’s a form of indulging and capitalizing in the pain of others, that is a form of voyeurism). Therefore, the imagery is simply a re-encountering of the words that are in four novels: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, Flora Nwapa’s Never Again, Kole Omotoso’s The Combat, and Ken Saro-Wiwa’s Sozaboy. These writers tell the war story from their different perspectives: as an observer, a post-memory subject, a victim, or a participant. They also approach it, even subtly, along the divisive lines of how they “felt” the war or, if you choose, how they “experienced” the war.

BM: In the book’s end notes, you mention “the Nigerian Civil War is no longer being taught in schools due to the exclusion of history lessons.” Canada is engaged in a process of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples to help promote healing from trauma endured from colonization and residential schools. Without any teachings to reconcile the effects of the Nigerian Civil War, what will the impact of this be to Nigeria’s younger generations? What role could social media play in helping or hindering reconciliation?

JV: History was abolished in Nigerian Primary and Secondary (high) schools between the 1980s and 2021. I think it was brought back to schools in 2023, which means there’s a lot of catching up to do. And thanks for that important reference to the “process of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples to help promote healing from trauma endured from colonization and residential schools.” This is important largely because history has a pivotal role to play in the decolonization process. You know the idea: if you do not know where you are going to, at least you should be able to understand where you are coming from. The absence of history means that many young people have lost their ways back and do not know how to return to their source, and that is an irreparable damage. But then again, there is the theory that the removal of history was to ensure that the violence of the state and its involvement in the war should somehow disappear. It would also mean that those who should be accountable become unaccountable. There’s a persistent form of disorientation, which means everything circles back to this sense of unresolved conflict. This conflict is not the only reference point, but it is as well a referential point for how we think of togetherness in Nigeria. In all of this, the unfortunate harm is to the state itself. I say this because the state lost a vital opportunity to create a natural, ongoing debate. Essentially, the inability to draw consciousness to Nigeria’s ethnic diversity has further deepened religious and political woes in the country. And that exactly is the impact on Nigeria’s younger generations: this overbearing sense of identity, in which the country serves its political purpose as a geographical entity, but the deep-rooted devotion and patriotism that should accompany it has no leg to stand on. And this is because they have not been shown who they are, such that they can reflect on the existence of others without constantly viewing co-existence as a threat. The problem of living with others is under a shadow of constant suspicion, and that is understandable. There’s also the social media influence, where news is dispersed without control, which means everyone becomes some sort of authority, and that definitely also has its own complications.

BM: Before Circumtrauma, you published five books: two poetry books, i am memory (2008) and The Birth of Illusion (2015); one novel, A Small Silence (2019); and one children’s book, Grandma and The Moon’s Hidden Secret (2022). What inspired you to write a book for children and where do you see it fitting in with your other writing?

JV: I had submitted it to a publisher who had excitedly put it up for indexing before we concluded the discussion. The central idea was to write at least one book in my indigenous language (Yoruba) and then translate it into English. I think the publisher approached me at the time, and it was important that the project connected with something I had in mind. And the project simply says I am a writer who is comfortable to tell her own stories, so it does fit.

BM: Could you tell us a little about the geometric system of Ifá? What got you interested in studying it? Was it fascination with the history of the traditional religion of the Yorùbá people, or any other divinatory teachings? Did your research influence not just Circumtrauma, but also your thinking more generally?

JV: I think the easiest way to explain the complex Ifá system is that it is central to the knowledge and spirituality of the Yorùbá people, for it is fundamentally a sophisticated coding system used for divination. Its entire framework is built upon 256 unique symbols, called Odu. The system’s geometric code is created, broken down into just two very simple concepts: a binary choice, which is the building block and the full sign, which is the code (or odu). For the binary choice, the entire system starts with a single, two-part result, similar to flipping a coin. The diviner uses palm nuts or chains to generate a count, which can only be one of two things, result A (Odd Count) and it is marked with a Single Line (I) and result B (Even Count) and this is marked with a Double Line (II). This is the basic, binary unit. To form a complete Odu sign, the diviner repeats that simple binary action eight times. Those eight results are then recorded to form a single symbol with two parallel columns, each having four lines. The first four results go into the right column. The last four results go into the left column. Since there are two possibilities (I or II) for each of the eight positions, the total number of unique codes available is 2 to the power of 8 (28), which equals 256. One way to conclude is that the Ifá geometric system is a simple application of binary math repeated eight times to generate 256 unique patterns of lines. And I grew up Yoruba, so there’s always going to be that fascination with the geometric system. I should confess that my interest is its aesthetic potential and its role as a theoretical framework for seeing, what desires a decolonising thought. That was what I focused on, because studying Ifá as a practitioner is a different ball game entirely. It is practically like going to school, and I cannot claim expertise in that. But I paid attention to its structure, because it serves poetry. It was used to convey poetry and philosophy, and histories, while also leaving the room for these stories to expand. And that is fascinating, right? And then again, anyone who grows up Yoruba, even when you don’t practice, Ifa is going to find its way into your everyday life. Anyway, my approach to writing is to look for the form that carries the right way in which the writing can be effective, or if you choose impactful. You want the reader to see, to hear, and to commit to the same things that made you write about the work in the first place.

BM: You are an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Toronto Metropolitan University, in the area of Creative Writing. Why did you pursue this field?

JV: Yes, I was many things before I became an Assistant Professor. I believe after dabbling in a number of things, I was convinced that I wanted to write and teach more than anything else in the world. While I was in Nigeria, I worked as an editor, both for a literary magazine and a publishing house. I did turn to full-time writing, but that didn’t turn out well. Then I wrote for newspapers as a freelancer for a while, and then I started my own Media/PR company with a friend. I became convinced I needed to return for my postgraduate studies, and I was doing the business thing along with school. When our major client left Nigeria, my business suffered a setback, and I focused on my graduate education. Years later, I would return to PR, but as an employee, but this time as a researcher and content consultant. I decided to apply for my PhD programme with the intention to teach, and the rest they say is history. I had written two books and submitted my novel for publishing before I moved to Canada, and being here opened up more stories to be told. It is a privilege to have stories to tell and be able to tell them.

BM: How does teaching influence your work as a writer and researcher?

JV: I teach creative writing, and I also research literature, so there’s a natural connection there. Or so I hope, when I wake up each morning.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Jumoke Verissimo is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Toronto Metropolitan University. She teaches and researches in the areas of creative writing (poetry, fiction, and non-fiction). Her scholarship extends to African literary criticism and literature, memory studies, traumatic affect and research creation.

Breanna MacElwain is a fine arts undergrad student at the University of the Fraser Valley. She currently lives in Chilliwack, BC.