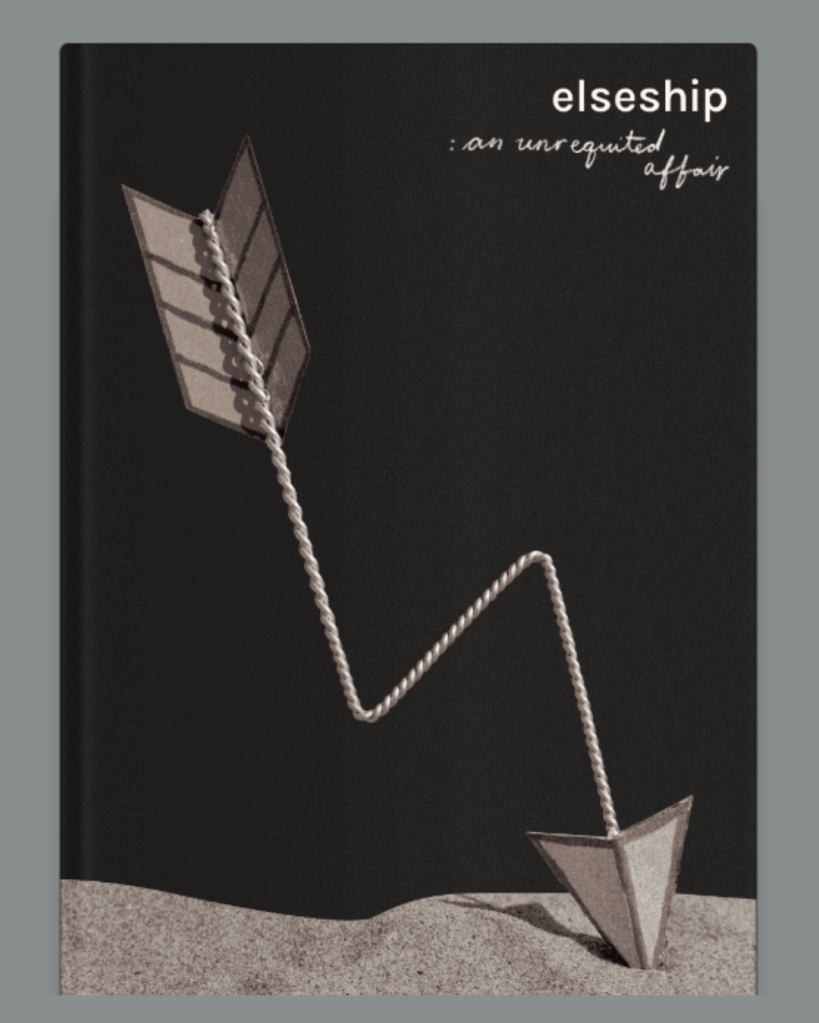

Interviewer Marlies Dubois talks with Canadian poet Tree Abraham about her poetry collection elseship: an unrequited affair out with Book*hug Press now!

Marlies Dubois: elseship is a deeply personal retelling of a relationship. At the beginning of the book you define it as an “unrequited love confronting friendship,” and you state that everything written in the book is “my side bias.” I know you journaled throughout the experience, but it made me curious about memory bias. How did you wrestle with bias while writing this book?

Tree Abraham: Unlike other manuscripts that I have written since that must draw upon memory, this book was birthed out of the manic impulse to process an all-consuming experience. Almost every interaction in elseship was written within the days following its occurrence because I needed the outlet of writing to self-soothe. That’s not to say that those words appear in the final book—because elseship is not a journal, it is an intentional transformation of feeling into art—but I had enough details to trust in my retelling. I also don’t consider myself someone with a great memory, but unrequited love so amplified and sharpened my attention that my memories surrounding it are much more vivid than other past experiences.

MD: Even though elseship is not a journal, it still feels like I’m reading someone’s most inner personal thoughts and feelings in a similar way. I think many readers who are going through an experience with an unrequited love would pick up this book. As someone who didn’t run away from that difficult time in the relationship and has had many years to process what happened, do you have any advice for someone going through their own elseship now?

TA: I sometimes get asked this question by people who are currently navigating similar elseships. The book is perhaps more self-help than anything. Every dynamic is so specific that I don’t feel like the portrait I have captured is easily templated onto any other two people. I don’t regret my choices, but I also would never wish others to emulate them. If there was a simple answer, I would have had nothing to explore in my writing.

MD: In both your books Cyclettes and elseship you blend writing with images. As someone with a Bachelor of Social Sciences in International Development and Environmental Sustainability and a Bachelor of Arts in Graphic Design and Illustration, what led you to writing? What is your process for integrating images into your books?

TA: I loved Harriet the Spy when I was young, so often I would say I wanted to be writer when I grew up like her, but I didn’t seek outlets for formalizing this dream or honing the craft. Writing had always been something secondary that was woven into my design projects. I most love design when it is in book form and spent many years creating work that recruited book arts techniques for its concepts. Graphic design can also be called visual communication. Its primary focus is making a complex world more navigable, so I see a book as a place where one can make a human experience more navigable. I don’t think of my books as being divided into text and image, but rather as the purest translation of my experiences to a reader, and sometimes the most effective language must be of hybridized forms.

MD: Throughout elseship you use images, definitions and metaphors about birds. You even write on page 258, “We are not normal, because we are rarae aves.” You include a definition of “rara avis: Latin for ‘rare bird’ or ‘strange bird’; a person or thing that is nonpareil, one-of-a-kind, exceptional, uncommon, unusual, wondrous, extraordinary.” On page 207, you include the definition of “leitmotif: a dominant or recurrent theme, idea, or object in a literary piece, performance, or person’s life.” It appears birds are one of the leitmotifs of elseship. Can you expand on why you chose to use birds throughout the book?

TA: I really don’t know how birds became such a central symbol, as with any of the other leitmotifs like rocks. It wasn’t intentional during the initial draft, but bird metaphors and references organically worked their way into my research and memories. I reflect on my use of metaphors in the final chapter of the book, how we tend to seek out signs when we are in need of meaning, when language falls short of our emotional landscapes. My home now is speckled with rock and bird artifacts. I also couldn’t say whether these collections began prior to elseship, or now have taken on a talismanic property because of it.

MD: Throughout the book you use words and images beautifully, but I also admire your use of white space throughout. On page 213, you write only “Words are never enough.” Then you leave page 252 completely blank and on page 253 you write only:

“Where is the love?

I know.

It’s everywhere.”

What is your process for using white space when writing, and how do you use it for emotional impact for the reader?

TA: My use of negative space is just one of many graphic devices that I intuitively weave into my writing because of my background in graphic design. I have heightened visual-spatial intelligence and years of training in considering how to provoke feeling within the limited real estate of a book cover, which is a chemical reaction between words and images, and substance and absence. The joy of interiors is how the reaction can be elongated across a sequence of pages. When I have heard other people read aloud passages from elseship, they mimic the cadence of my voice, and that is because I have built that pacing into the text’s formatting. Poets do this as well; I am borrowing from centuries of other artists. I think when dealing with heavy subject matter, readers need some guidance—on when to take a breath and step away to draw their own conclusions or squint harder to make connections. The white space is there to say slow down, linger, be gentle on yourself.

MD: In the beginning of the book, you write, “I must not live in this book. Once recorded, I should abandon what is not written and move beyond it, back into an unwritten future.” You also write, “This year I needed this story, I still do.” I found both statements very interesting. What are your thoughts on them today, now that the book has been published? Have you abandoned what was not written?

TA: It is impossible to say how much of where I am today can be attributed to time or having published a book that has unburdened me of carrying the story in memory. I can remember what is not located in the book from that time, but also the six unwritten years that followed. However, I have abandoned not only what was not written, but also what was written and now dwell mostly in the present. Perhaps had I not agonized over making meaningful art of that experience, it would haunt me. I suppose I am grateful to have elseship as some kind of gravesite that honors a life that my body walks free of.

MD: In the book, you share some of the recommendation forms you asked people in your life to fill out, as well as a list of your own. You state that you did this to “expand your influences through the obsession of others” and to inspire your next decade. If you were to fill out the form of recommendations in your book today, what would they be?

TA: In the book I collated of recommendations forms, at the beginning I included one that I had completed as a way to mark my thinking as I approached thirty, and then I included a blank form at the end to complete decades later. The exercise is a bit trickier when done generically because my friends were not completing the forms for themselves, but in response to what they knew of me. But if I am to play along and redo the form for an unknown recipient, maybe this year it would be:

Book: Italo Calvino’s The Complete Cosmicomics

Film: Perfect Days

TV show: Dying for Sex

Song: Basia Bulat’s“The Shore (The Garden Version)”

Person: see elseship

Place: Wellfleet

Thing: a bicycle

Food: oyster mushrooms, other mushrooms

Activity: wild swimming, bread knotting art

Word: prelapsarian

Quote/Concept: Too many, every day! Of late, this passage:

“Consider the subtleness of the sea; how its most dreaded creatures glide under water, unapparent for the most part, and treacherously hidden beneath the loveliest tints of azure. Consider also the devilish brilliance and beauty of many of its most remorseless tribes, as the dainty embellished shape of many species of sharks. Consider, once more, the universal cannibalism of the sea; all whose creatures prey upon each other, carrying on eternal war since the world began.

Consider all this; and then turn to the green, gentle, and most docile earth; consider them both, the sea and the land; and do you not find a strange analogy to something in yourself? For as this appalling ocean surrounds the verdant land, so in the soul of man there lies one insular Tahiti, full of peace and joy, but encompassed by all the horrors of the half-known life.” —Moby-Dick

MD: elseship explores the feelings of unrequited love in a unique way. I found that it wasn’t just romantic, but also when one friend feels a deeper friendship than the other. Have you found that, by opening up about these feelings, you have strengthened your connections with others in the community?

TA: If you mean my personal community, I suppose I was always a vulnerable person, but certainly in the years around when elseship took place and I turned to those around me for answers with more fragility than what they would have typically known of me—because I had become more fragile, more tender, and since, know more empathy—those relationships have come to be ones of immense compassion and mutual care. As for some wider community of strangers, Wendell Berry contends that “community” must involve a place and its people, a placed people. He rejects the idea that genuine community can scale beyond one’s immediate environment. In that way, while it gladdens me to hear from readers who have felt less alone because of my book, I wouldn’t say my daily identity is situated within these broader spaces. Jenny Slate did this fantastic little interview with Entertainment Weekly back when she was promoting her first book Little Weirds. She talks about how people wonder how she has the courage to be vulnerable, and she says that she doesn’t think she is more or less vulnerable than anyone else, but that she has decided that it feels better to let it out rather than keep it in. I’d like to think I live my life and make art similarly, and perhaps by doing so I am quietly inspiriting others to find their own respectful way to be vulnerable amongst their placed people.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tree Abraham is an Ottawa-born, Brooklyn-based writer, art director and book designer. Her authorship experiments with fragmented essays and mixed media visuals. She is the author of two creative nonfiction books: Cyclettes (a New York Times editor’s choice, published by Unnamed Press, 2022) and elseship (Indie Next pick, published by Soft Skull Press, 2025).

Marlies Dubois is an English undergraduate student at the University of the Fraser Valley. Her short film, OASIS, that she co-wrote, received grants from TELUS STORYHIVE and Creative BC. She lives in Ladner, B.C. with her husband and two children.